(published in french in issue n°29 of journal Les Mondes du Travail, March 2023, pp.187-210)

Stephen Bouquin (Professor in sociology, Paris-Saclay)

“Marx said that revolutions are the engine of history. Perhaps things are different. It may be that revolutions are the act by which humanity travelling in the train pulls the emergency brakes” (Walter Benjamin, Thesis XVIII on the Concept of History, quoted by Michael Löwy (2016)[1] .

“Even an entire society, a nation, or all existing societies simultaneously taken together, are not owners of the land. They are merely beneficiaries of it, and must bequeath it in an improved state to succeeding generations as boni patres familias [good fathers of families]” (Capital, vol. 1 ([1867]; London, 1976), p. 637.

Introduction

The ecological crisis has become increasingly important to the point it incorporates almost all other issues, be they the mode of governance, social inequalities, everyday life or simply economic organisation and this from top to bottom of society. But the theoretical understanding of this surge has yet to be sufficiently developed. Our article aims to contribute to a clarification of how to deal with the ‘ecological question’ from the standpoint of living beings and life and this both on scientific and practical terms.

What does the ‘ecological crisis’ is telling us about itself? This will be our introductory point. How should we think about the meaning of ‘nature’ and of the relationship to be established between nature and society? While dualistic approaches can be criticized for having been used to justify the domination of nature by mankind, should the alternative be a ‘monistic’ approach that merges nature and society, thereby treating them on equal levels? We do not think so, and in this second point we will stress the importance of an epistemological orientation based on critical naturalism that is both materialist and dialectical. In a third point, we will present a series of analyses that recognize the primary role of the capitalist system in the ecological crisis. This critique of the ‘Capitalocene’ gains from integrating that of patriarchy, which will be our fourth point that presents materialist ecofeminist approaches. In a fifth point, we will return to the category of ‘living labour’ as a both natural and social ‘corpo-real’ entity. Mobilizing living labour at the core of analysis is necessary to articulate the labour and the social question with the ecological question in view of formulating proposed actions aimed at moving towards an ‘economy of the commons’. In conclusion, we will briefly return to the urgency of the ecological crisis to emphasize the importance of a systemic shift and the construction of a common horizon.

1 – What is the ‘ecological crisis’ telling us about itself

One of the main difficulties in understanding the ecological crisis lies in the polysemy of the concepts used. Indeed, the notion of ecology – etymologically Oikos (habitat or house) and logos (science/discourse), i.e. the science of habitat – can mean many different and even opposing things. It was coined for the first time in the 19th century by the German biologist Ernst Haeckel, who gave the following definition in his book Die Generale Morphologie der Organismen (1866): ‘By ‘ecology’ we mean the science of the relationship of organisms with the external world, in which we can recognise in a broader sense the conditions of existence which may be favourable or unfavourable’ (quoted by Deléage, 2007: 63)[2]. For Haeckel, such definition, rather neutral at first glance, was entirely compatible with absolute reactionary views that favoured the cleansing of humanity in the name of a pseudo-scientific theory of the survival of the fittest[3]. Logically, Haeckel advocated eugenics with the mass killing of disabled or people or those declared psychological insane. He also advocated the cleansing of society through the infliction of a quick-acting, painless poison. Indeed, it is no surprise that Haeckel was very popular among the Nazi intelligentsia.

The American zoologist and anthropologist Madison Grant (1865-1937) is another figure whose ecological thinking was resolutely reactionary. Grant was inventor and promoter of the National Parks in the United States of America and believed that confiscating land from Native Americans and denying Afro-Americans any access to property was absolutely essential to the ‘preservation of the wild beauty of nature’… These historical facts remind us that ecology is not spontaneously progressive (nor reactionary) but that it can also be expressed in the manner of eco-fascism, eco-liberalism or eco-socialism…[4] Of course, this ideological heterogeneity of ecologism (or even environmentalism) in no way prevents the ecological crisis from vociferously occupying reality. Thanks to the work of many scientists (climatologists, glaciologists, wildlife biologists), the very existence of a crisis is now widely acknowledged[5]. In the 1970s, attention was focused primarily on the problems of pollution and so-called overpopulation of the earth (Meadows, 1972), which charged the ecological discourses with a neo-malthusianist spirit – a tendency that has far from disappeared, incidentally. It was only after Rio’s Summit in 1992, when the effects of climate change became tangible, that carbon dioxide emissions became an important issue for environmentalists.

Nowadays, the ecological crisis is mainly seen through the lens of the climate crisis. Large sections of population are becoming aware of this following the succession of heat waves, multi-year droughts, wildfires that are striking entire regions at an accelerated pace, while other regions or sometimes the same but at other moments, may face torrential rains, causing large-scale floods that sweep away entire villages or put cities under water in torrents of mud [6]. Less acknowledged is the fact that the ecological crisis has now reached such a scale that it triggers other disruptions that have their own dynamics. One of these is the slowing down of oceanic sea currents, which is disrupting the temperatures and rainfall in western Europe and the East coast of North America. Another illustration is the ‘albedo’ effect of the melting ice cap, which reduces the reflection of sunlight and accelerates global warming, the acidification of the whole parts of the sea and the mortification of terrestrial ecosystems, which are increasing the fall in biodiversity and provoking the sixth mass extinction [7] .

It should be recalled that the pandemic and the climate crisis are not separate, parallel phenomena, but an aggregate with various internal temporalities. Coronaviruses will not directly affect the climate, but pathogens can develop in connection with climate change… For example, it is known that drought and deforestation in South East Asia has caused wildlife to migrate massively – not only insects (mosquitoes, grasshoppers) but also bats, whose primary food source are made of insects. This caused bat species to migrate from Indonesia to more northern area’s as far as China or from North Africa towards Germany and Poland… This kind of migrations may of course bring together living species that were not used to cohabit same ecosystems, humans as well as other animals, what will increase the spill-over of pathogens. In addition to these aspects, we should also recall that circuits of industrial farming of animals are both vectors of market dependence and of use diffusion of pathogens. Critical microbiologist Rob Wallace demonstrated how gigantic industrial livestock farms increased the frequency of mutations, zoonoses and large-scale infections. Every year, bird flu and swine flu wreak havoc in thousands of factory farms, leading to eradication of massive live-stocks of animals. The biological risk management of havoc include massive use of antibiotics which has led to increasing resistance towards bacterial infections, heralding the advent of new diseases and risks of contaminations that can affect both animal and human populations on global scale.

In answer to the question of what the ecological crisis is telling us about itself, we can answer that it exposes the human causes (the Anthropocene) and that it invites us to consider the underlying global and systemic dynamics as well as to recognize that the path upon which we are could be a ‘runaway’ that will lead to globalized disaster if nothing is done while there is still time.

2 – Nature and society: the limits of dualism and monism

Should one refer to ‘nature’, the ‘natural environment’ or to ‘eco-spheres’? Or simply the ‘Planet Earth’ as a habitat for to all kinds of life? These recurring questions require sounding answers because this will help us to deal in a more systematic way with the unravelling ecological crisis.

For post-structuralists, who recognize only (or mainly) the performative character of discourse and representations in the making of the world, nature should be understood as a symbolic construction, a view of the mind. For others, there will always be an ontological difference between physical environments, the organisms that may inhabit them, and conscious and reflexive human activity. According to such a dualistic conception, which separates nature and society, human activity is thought as external to nature, which then can be seen as a ‘natural environment’, that certainly surrounds us but also one that can be mastered or domesticated. For a very long time, this dualism has legitimated a certain indifference towards the consequences of human action upon it. Such a dualistic vision can certainly be found in the writings of René Descartes, for whom the universe is made up of physical substances, while the human being is made up, first and foremost, by a spiritual and immaterial reality. Sociology has for long time followed this path with someone like Emile Durkheim claiming that nature and culture are distinct, including among human beings. Indeed, following Durkheim, woman are ‘natural beings’ somewhat removed from reason, while the man (in the masculine) is a product of culture. According to his logic, women are responsible for reproduction and the preservation of Domos, the home, while men are in charge of production, creation and governance. While some recent French sociologists (Lallemant, 2022) see reasons to relativize critique of Durkheim’s naturalization of women, others (Gardey and Löwy, 2002; Gardey, 2005) support the need of a radical critical examination of sexist naturalism within social sciences [8] .

More generally, it should be recalled that the dualistic conception of the human/nature relationship has been and remains the subject of recurrent criticism by the ecologist movement. However, this criticism is very often based on a ‘monistic’ conception, which tends to deny any interrelationship between humans and nature, which could also have the consequence of relativizing human responsibility in the preservation of the natural environment or worse, considering that nature is ‘taking revenge’ upon its main destroying factor (Larrère, 2011). Indeed, these monistic conceptions tend to absorb all distinctions between nature and culture, between environment and society, and basically proclaim that we must naturalise ourselves again…

While eco-fascism claims to have a monistic conception in which humans are entirely naturalized as having to live in harmony with natural laws, in reality it seeks to take the subjugation of nature and humans by other humans to a level never achieved before (Dubeau, 2022; François, 2022). Still, we should avoid unfair accusations and refuse to claim that any monistic vision of the human/nature relationship is necessarily reactionary. This is, in any case, what anthropological studies of Amerindian, Oceania and Southern African living communities have demonstrated (Sahlins, 1962; 2008; Graeber and Wengrow, 2021). In these communities, where egalitarian relations prevailed at a certain distance from patriarchy, social relations were organised in close symbiosis with the natural environment. The accumulation of surplus was actively thwarted (cf. the Potlatch, nomadic agriculture, the refusal to accumulate and hoard, etc.) and religious spiritualities, whether they are shamanic or animistic, reflect this integration into a ‘natural environment’ in which life is organized in close interdependence. This also explains why, both materially and symbolically, why these communities tended to preserve a balance between the social activity of humans and what is referred to as a ‘natural environment’. Such a monistic naturalist position can also be found in the radical environmentalist movement that identifies itself with deep ecology, that presents certain alternative experiences and mobilisations as an expression of nature itself (‘we are not defending nature, but we are nature defending itself’ as the motto of the Extinction Rebellion action network).

Sometimes this monism translates itself into an open refusal to even speak about nature. From this perspective, which can be found in particular in the work of the anthropologist Philippe Descola, nature does not exist ‘in itself’ and is nothing more than a metaphysical device that European civilisations have invented in order to emphasise a separation between human activity and the world around it; a world that has become a reservoir of resources, a domain to be exploited, a space for predation [9]. Since human activity is an integral part of the Earth’s vast ecosystem, Descola believes that the most urgent task is to seek after ways of ‘inhabiting’ the world that are no longer destructive of the ecosystem. However, in addressing the issue of change, monistic readings of the relationship between society and nature also reveal that they have not fully resolved the issue on a theoretical level. The different ways of inhabiting planet earth are certainly based on social customs and norms, but also on a mode of social organisation and, incidentally, a mode of production. Both intellectually and practically, we are faced with the existence of a social world that is organized according to a systemic logic, which brings us back not to nature but to society and to the relations between these two inseparable and interdependent realities.

Bruno Latour is undoubtedly the intellectual who has expressed an ongoing ambition to rethink the world and the relationship that humans have with their environment, whether it be made of artefacts or more broadly encompassing the whole of the earth’s ecosystem. For Latour, nature is not a victim to be protected, but ‘the one which possesses us’ (Latour and Schultz, 2022, p. 43). It is therefore necessary to refuse to think that humans can act from the outside on a nature from which they would be separated. It is in Politiques de la nature (1999) that Latour clarifies his position, close to certain developments in post-structural anthropology, and in particular that of Philippe Descola. His main proposal is to install nature as the primary subject of politics, to make it a leading political actor and to definitively remove it from its status as an object. He thus extends his earlier work sur as Laboratory Life (1979) or We have never been modern (1993) in which he placed human action within a network and the action of objects on the same level. Men and environment are one and human beings must adapt as much as their environment changes, while having a direct and indirect action on the human.

As R.H. Lossin states in the radical journal Salvage [10], Latour may seem convincing in his more general formulations such as the rejection of the separation between nature and culture, the critique of the main analytical categories of modernity or the recognition of what technology does to us rather than what we do with it, his approach is far from unequivocable. Indeed, his theoretical framework raises several fundamental criticisms. One of these is the fact that Latour sees the asymmetry of human/non-human relations as a kind of primary misunderstanding of reality. However, the opposite is true since this asymmetry is very real and highly problematic in the way it exists. By considering all aspects of life as a network of interacting objects, his theorization has become a kind of textbook of reification or Verdinglichtung of nature and ultimately offers nothing but empty materialism (Lohsin, 2020).

In the twilight of his life, perhaps because he was recognizing the limits of his earlier positions, Latour eventually pulled the ‘new geo-social class struggle’ out of his hat (Latour 2021, Latour and Schultz, 2022). What is at stake is a struggle of ideas based on a ‘class’ that is based upon sharing the same ‘cause of habitability’ of the earth [11]. In his last writings, Latour evoked the urgency of a ‘new climate regime’ in which the conditions of habitability would be the utmost priority. Still, we can ask ourselves if this the fundamentally answer to the problem that we are facing, i.e. capitalism. For Latour, this is not the issue, since anti-capitalism mean for him nothing more than a vague catchword that prevents us from thinking complexity, since the goal ‘is not to replace the capitalist system but to recover the Earth’[12]. As a matter of fact, Latour has constantly neglected a critique of capital and capitalism, and even when he did mention it, mainly in interviews, they become an umbrella notion designating big money and financialization.

Some may regret this avoidance of a critique of capitalism but maybe we should try to grasp also the reasons for these silences. If capital remained an analytical blind spot for Latour, it is not only for ideological reasons but above all for theoretical and conceptual ones. Since Latour understands reality as a collection of objects, he simply did not grasp the deep reality of capital, since the latter is not an object, nor a thing but a social relation or, to put it another way, a ‘real social abstraction’ that is not always visible as such nor observable[13].

To a certain extend we could say that the pandemic revealed in its own way the connection between nature and society. Andreas Malm made this point very clear: ‘Is the Covid 19 pandemic nature’s ‘revenge’? Latourians, posthumanists and other hybridists can be counted on to give the corona an anointing of agency. But the ontological difference between humans and non-humans remains: bats were not tired of the forest, pangolins did not choose to be sold, and the SARS-CoV-2 micro-organism did not develop a plan to infiltrate ventilation systems or aircrafts. Only humans think: there is oil in this swampy subsoil or if we raise more cattle, we can sell more…’ (Malm, 2020: 173)

These somewhat abrupt formulations are based on the assertion that nature and society must be thought of as interacting as well as interconnected with each other, as a contradictory unity composed of both relatively distinct and interdependent realities. This is also what French sociologist Jean-Marie Bröhm proposed when he devoted a book to an in-depth examination of the principles of dialectics (Brohm, 2003), framing historical materialism both as critical naturalism and social constructivism: ‘[it is] a unitary science insofar as it studies, not society and nature in their respective autonomy, in their ontological separation, but in their reciprocal interaction (…) For Marx and Engels, there is only one science, the one that studies the movement of society in its contradictory relations with nature – which both carries it along by offering it resources but also destroys it by overwhelming it with various catastrophes.’ (2003 : 140).

Nevertheless, according to Bröhm, it is necessary to recognize that this dialectical unity between nature and society is in the process of shattering: ‘(because) it is becoming a double destruction: first, the destruction of nature – of the environment, of the fauna and flora in their biodiversity – under the devastating expansionist effects of the capitalist mode of production; second, the gradual destruction of society as a result of the relentless exploitation of natural resources and the massive pollution that ensues’ (Bröhm, 2003: 141). Thus, for humanity, there is no other solution than to ‘protect the earth’ and to rehabilitate its own naturality, for itself and for future generations, which Marx summed up very well when he wrote: ‘From the point of view of a higher organisation of society, the right of ownership of certain individuals over parts of the globe will appear as absurd as the right of ownership of an individual over his neighbor’ (Marx, 1974: 159).

3 – Some thoughts about the fertility of an eco-marxist critique of the ‘Capitalocene’

For a long time, Marx and Engels were perceived as thinkers that favoured the unparalleled growth of the productive forces with the plenitude of abundance as the main means to achieve communism. It is not difficult to find in their writing arguments in favour of this perception, especially in the chapters that ends third book of Capital. Of, course, such perception is also nourished by the harmful experience of a bureaucratic USSR that was entirely oriented towards productivism and was almost as deaf towards social needs and use value as capitalism is blind, since it only recognize exchange value and profit. At the same time, one should not forget that Marx (or Engels) defended the assertion that both labour and are the only sources of all wealth, as can be read in the Critique of the Gotha Programme. However, recognizing the contribution of nature in the creation of wealth does not directly imply making a careful use of it, which justifies, according to eco-socialist thinkers such as Daniel Tanuro and Michael Löwy, a critical assessment of the too many silences of Marx and Engels on this question[14].

Other authors are less circumspect in their recognition of an ‘ecological Marx’. The most well-known of them is of course John Bellamy Foster, professor of sociology at the University of Oregon, who challenged in his book Marx the Ecologist (2011) a number of failings falsely attributed to Marx in relation to ecology, such as his failure to recognize the exploitation of nature, the existence of natural limits, or the variable character of nature. Foster was among the first that initiated a re-reading of Marx’s work that has identified some key concepts to better understand the problematic interrelationship between nature and society that is specific to the capitalist mode of production.

Following J.B. Foster, the ‘ecological Marx’ relied his understanding of the destructive and transforming character of capitalism on the critical assessment of second agricultural revolution made by Justus von Liebig. The German chemist was scandalized by the intensive use of chemical fertilizers, since this would deplete soil fertility, which would trigger the use of additional fertilizers such as guano and bones from the battlefields of Europe (containing potassium, nitrogen and phosphor). This brought von Liebig to extend the concept of metabolism (Stoffwechsel), previously limited to intra-corporeal biological processes, to all kind of natural systems. As an avid reader of scientific literature, Marx realized that soil fertility is not a pure natural phenomenon but socially produced under changing conditions, since natural realities (soil composition, rainfall, erosion, etc.) constantly interact with social conditions such as agricultural techniques. This is why Marx adopted the concept of metabolism to understand how nature is functioning in larger perspective and extended it to social processes, relating it at the same time to their natural environment.

Foster main thesis is that Marx elaborated the lineaments of an understanding that allows for the identification of the ecological crisis inherent in the capitalist regime, which he refers to as the Metabolic Rift taking place in the interdependent process of social metabolism and a metabolism prescribed by the natural laws of life itself. The ‘universal metabolism of nature’, the ‘social metabolism’ and the ‘metabolic breakdown’ are of crucial importance in modeling the complex relationship between socio-productive systems, particularly that of capitalism, and the wider natural/ecological systems in which they are embedded: ‘This approach of the human-social relationship to nature, deeply interwoven with Marx’s critique of capitalist class-based society, provides historical materialism with a unique perspective on the contemporary ecological crisis and the challenge of transition.’ (Foster, Clark and York 2010: 207.)

While Foster was the first to put forward such a re-reading of a fully ecological Marx in an article published almost a quarter of a century ago in the American Sociological Review (1999), other authors, such as Jason W. Moore (2000, 2011), were quick to follow him, but differed on important points. For Jason W. Moore, the ‘metabolic rift’ did not take place at the beginning of the 19th century but much earlier, in the 17th century, when the crisis of feudal serfdom in England freed a component of the peasantry from the obligation to pay tribute or to perform work tasks for their lords. This was coupled with the privatisation of the commons (via enclosures) and the use of arable land as pasture necessary to sustain a massive production of wool that merchants exported to Europe in late Middle-Age. The colonisation of the New World and the development of sugar cane plantations provided a caloric-rich resource that compensated the scarcity of food provoked by the expansion of pastures. But such a ‘remedy’ created the need for disposable workforce which was responded into the development of the slave system in those colonies[15]. This explains, according to Jason W. Moore, why the ‘metabolic rift’ is connected to the imperial ambitions of the British crown, the colonisation and, more indirectly, of the massification of slave trade.

Geographer and economist David Harvey has not been silent on the ecological question (Harvey, 2015: 222-263) even if he tended to underestimate up till recently the irretrievable character of the ecological disaster. Harvey remains also quite vague about the nodal position of this metabolic rift. Instead of this, he propose to understand capitalism as an ecosystem in itself, involving both capital and nature that are produced and reproduced through systemic interrelated dynamics. Capital, as a specific (historical) form of human activity has not only exhausted nature but also (re)metabolizes it, with the logic of profit and the law of value as the principal organizing principles. Nature is thus not only exploited and exhausted but is also internalized in the circuit of accumulation (Harvey, 2015: 246.). This is quite obvious since we know that both seeds and plants can be genetically modified in order to expand the volume but also the corporate control over grain trade. Local self-sufficient agricultural production is replaced by a global trade that is integrated into the circuits of valorisation. What is common to John Bellamy Foster and David Harvey is that both are stating that capitalism ‘metabolises’ nature and is becoming itself a reality that is metabolised by nature, but in a contradictory way[16]. On a more strictly economic level, Harvey has linked global financialization of capital to the extractivist and predatory pressure of neoliberal capitalism, which he summarizes as ‘accumulation by dispossession’, analogous to the primitive accumulation of capital based on coercion and predation. Both the growth of fictious capital, speculative bubbles, the spiral of debt is pushing capital accumulation towards a headlong rush to find new and more sources of speculative assets, no matter if this means the frenetic and predatory acquisition of arable land, of minerals and, more broadly, of all kinds of potential natural resources buried in the subsoil or at the bottom of the oceans.

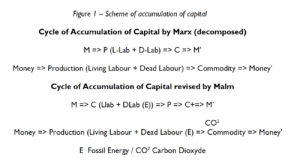

Critical understanding of the ‘Capitalocene’ shouldn’t remain superficial on his historical understanding of it. This is why the key role played by fossil fuels in the upcoming ecological disaster is also a crucial aspect. Swedish professor Andreas Malm of Lund University is a strong advocate of the concept of ‘fossil capitalism’. In Fossil Capital. Global Warming in the Age of Capital (2016), Malm presents a socio-economic historical analysis of the factors that led to the intensive and extensive use of fossil fuels. To him, the concept of the Anthropocene, while it has the merit of naming the problem, is entangled in a millennia-old narrative of humanity that is basically a mad pyromaniac arsonist. But if we want to understand global warming, it is not the archives of the human species that need to be investigated, but those of the British Empire, says Andreas Malm. He demonstrates that the steam engine was, in the second half of the 18th century, an essential tool for disciplining workers. Indeed, in the English textile industry, the machine developed by James Watt quickly supplanted the abundant and cheaper hydraulic power used by a vast dispersed number of small scaled manufacturing houses. Malm explains that in order to understand this paradoxical fact of mobilizing a much more expensive energy, one has to integrate the agency (the capacity to act) of ‘living labour’. With hydraulic power available in many places but of variable quantity, the location of the textile industry was necessarily decentralized and moderate in size, forcing entrepreneurs to bring to these rural areas cohorts of labour that were often recalcitrant in their commitment to work and demanding in terms of pay. The steam engine made it possible to expand textile factories and locate wherever specially in urban agglomerations, exactly where thousands of impoverished workers tried to make a living and a reserve army was ready to replace those that were reluctant. For Malm, ‘fossil capital’ allowed the limits of surplus extraction and profit to be pushed further, both on the side of living labour as on that of natural ecosystems (predation, coal mining). These insights have led him to elaborate a revised version of Marx’s cycle of capital accumulation, which he represented schematically as follows (see Figure 1).

After coal, it was the turn of oil and its by-products, extracted on an unprecedented scale and propelling hundreds of millions of thermal engines and mass consumption goods– cars, household appliances – which have led us on the track of a global ecological disaster.

In Corona, Climate and chronic emergency (2020) Andreas Malm revisited the links between the ecological crisis and the systemic logic of the Capitalocene. Malm explains that capital has no intention of destroying the complex cellular structures of wild nature and that it has no intentionality in its efforts to generate profits. No, capital ‘acts’ in this way because it simply has no other way to reproduce itself:

‘Fixation and absorption are in the DNA of capital. The moment these cease to accompany the process of accumulation, the reproduction of capital ceases to exist. Unlike other parasites, capital cannot simply vegetate in the fur or veins of other species for millions of years of co-evolutionary equilibrium. It can only subsist by expanding and, in this sense, it exhibits a kind of permanent pandemicity. Once capital escaped from its reservoir host, i.e. the British Isles, it began the enormous historical process of subsuming the wilderness of this planet, whether in the form of a palm oil plantation, a bauxite mine, a wet market or a chicken farm. All these entities and countless others represent the wilderness drawn into value chains. (Malm, 2020: 76)

Like a virus that multiplies and circulates, capital is a kind of meta-virus – ‘the godfather of all parasites’. Following David Harvey’s understanding of capitalism, Malm reminds us that the accumulation of capital is based on the permanent appropriation of space and time, which proceeds by a double compression, that of space and that of time. Indeed, capital constantly seeks to shorten the rotation cycle of its accumulation: the faster commodities will be sold, the faster an investment can be paid back and ultimately the greater the profits. Capital seeks also to cancel out space by linking territories and populations through trade, migration flows or technical devices in order to enlarge markets and to integrate them into a glow flow of commodities and accumulation. But that’s not all, the capitalism also requires the enlargement of wage labour and the reproduction of labour power, which remains an activity that is carried out almost exclusively by women in an unpaid way. This brings us examine in the following section patriarchy and the sexual division of labour.

4 – Domestication of nature and patriarchal domination: the Capitalocene through the prism of the ‘Patriarcocene’

Friedrich Engels, in his work on The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State, succeeded in elaborating the lineaments of a theorization of the women as ‘the first oppressed class’. While the second feminist wave of the 1960s-1970s produced much more systematic elaborations, the term ecofeminism was first enunciated by Françoise d’Eaubonne in Le Féminisme ou la Mort (1974) to signify that the domination of nature and women are historically linked [17]. In the Anglo-Saxon world, thanks in particular to Carolyn Merchant, author of The Death of Nature (1980, 2021), ecofeminism developed quite rapidly in social sciences. Merchant considers that women’s identification to nature dates back well before the Neolithic revolution and was based on fertility imagery associating the earth with a beneficent and nurturing mother [18] . The colonisation of the New World and the slave trade represented a qualitative change also because it coincides with another regime of truth that is based on scientific rational claims.

Ecofeminist theory shows us how the ideology of the forces of production originated in a hetero-patriarcal, racialist and speciesist model of rationality. Following Valerie Plumwood (2012), an Australian philosopher influenced by Critical Theory. [19], human existence has been associated in Western culture with productive labour, sociability and culture while separating them from forms of labour considered as secondary from forms of collective property such as the commons. This is also demonstrated in the fact that classical political economy defines reproductive labour as non-labour, i.e. as value-free activity even if it responds to social need while commons are seen as resources of value that have yet to be realized (see also Barca 2010).

Maria Mies is certainly a central intellectual figure in late 20th century ecofeminism. Mies argues in her Magnus Opus Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale (1986) that feminism must go beyond the critique of the sexual division of labour, incorporating into the framework of analysis the condition of the women in the periphery of the capitalist world-system in order to identify ‘the contradictory policies concerning women that have been, and still are, promoted by the brotherhood of militarists, capitalists, policy-makers, and scientists in their effort to maintain a model of growth’ (Mies, 1986: 3). Whereas classical political economy has conceptualized labour in opposition to nature and women, i.e. as a productive activity actively shaping the world by giving it value, Mies considers as labour any activity that participates in the production of life and which ‘must be called productive in the broad sense, the production of use values for the satisfaction of human needs’ (Mies, 1986: 47). Mies’ argument being that the production and reproduction of life, or subsistence labour, carried out mainly in unpaid ways by women, if not by slaves, peasants and colonized subjects, ‘constitutes the perennial basis on which capitalist productive labour can be built and exploited’ (Mies, 1986: 48). Since it was not remunerated, its capitalist appropriation could only be achieved in the last instance through violence or the intervention of coercive institutions. The sexual division of labour was based neither on biological nor economic determinants, but on the masculine monopolisation of (armed) violence which ‘constitutes the political power necessary for the establishment of lasting relations of exploitation between men and women, as well as between different classes and wage earners’ (ibid.: 4).

The foundations of capital accumulation in Europe were placed on a parallel process of conquest and exploitation of the colonies, slavery and the exploitation of women’s bodies and productive capacities. At the same time, European women of different social classes – including those involved in settlement colonialism – were subjected to a process of housewifization, limiting their existence to the function of a housewife. As a result, women were progressively excluded from political economy, which was linked to public space, and enclosed in “the ideal of the domesticated and privatised woman, preoccupied with love and consumption, dependent on a man who had become the male breadwinner’ (Mies, 1986: 103). However, this housewifization also mean that women represent the vast majority of the world’s reproductive and caring classes. Although the status of women is obviously divided by cleavages of class and racialization, it is also true that women can be seen as part of the global proletariat whose bodies and productive capacities have been appropriated by capital and the institutions that serve it.

As a matter of fact, the combination of ecofeminism with historical materialism makes it possible to articulate reproductive labour and any labour activity that consists of supporting life in its material and immaterial needs with a critique of the Capitalocene. The recognition of the nodal character of reproductive labour leads us towards a critique of capitalism that is instrumentalizing as well as commodifying life for ends other than life itself, whether it be the preservation of power relations or the imperative valorisation of capital. Today, it is clear that reproductive labour is increasingly submitted to commodification and rationalization, both processes by which it is incorporated into the circuits of capital accumulation. Capitalism thus mutilates the potential for improving life by transforming reproductive labour and care into instruments of accumulation and sources of profit. These processes exhaust both care-giving people (as workers or not) workers and the environment, extracting ever more surplus labour and energy and leaving workers exhausted in terms of their physical and mental resources. As Tithi Batthacharya (2019) aptly summarises: ‘The pursuit of profit is increasingly in conflict with the imperatives of life creation’.

5 – From the critique of real existing work to the defense of ‘living labour’

Following Roy Bashkar’s ‘critical realism’ [20], we will take as the starting point for our reflections labour and work as they actually exist and not as we would like them to be, as a ‘fetish’ or an anthropological reality understood in transhistorical terms. Moreover, privileging an analysis of work/labour based on a generic or ideal-typical form, whether it be artisanal or creative work, is not very fruitful from a heuristic viewpoint. Certainly, some forms of work can give rise to self-realization, but these situations remain quite exceptional or are nowadays suffering social degradation (socio-economic insecurity, debt bondage, dependence towards the market). Public service work is not immune to these regressive trends; consider for example the effects of New Public Management, digitalisation or austerity policies. Moreover, basing the analysis on work and labour as it objectively exists and not as it ideally should be, allows us to revisit the issue from a conceptual point of view, which is necessary to clarify what ‘ecologization’ of work might mean on a practical level.

It should be recalled that an impressive number of factual analyses quite close to this ‘critical realistic approach’ are to be found in Engels’ and Marx’s writings. Friedrich Engels, in his Letters from Wuppertal (1839), gives an extensive account of the living and working conditions of the textile workers in Barmen, a small town in Rhineland-Westphalia which was also his birthplace:

‘Labour is carried out in low rooms where one breathes more coal fumes and dust instead of oxygen. Workers are starting to labour, in most cases, at the age of six, which can only deprive children of all strength and joy of life. (…) The weavers, who have their own loom in their house, work from dusk till dawn or even into the night, straining their backs and drying out their spinal cords in front of a hot stove. (…) If one can find robust people among the craftsmen, like the leather workers born in the region, three years of this life are enough to ruin them physically and mentally and three out of five died from alcohol abuse. All this would not have assumed such horrible proportions if the factories were not exploited so recklessly by the owners (…). Terrible poverty prevails among the lower classes, especially among the workers in Wuppertal; syphilis and lung diseases are present in almost every family. In Elberfeld alone, out of 2,500 children of school age, 1,200 are deprived of education and grow up in the factories – simply so that the manufacturer does not have to pay adult workers, whose place they take, which would double the wages that are paid to a child.’

A few years later, Engels systematized his exercise of sociological investigation before publishing The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845). Numerous detailed descriptions – based in particular on medical reports – mention the excess infant mortality, diseases and deformities linked to exposure to chlorine, arsenic or lead. Karl Marx, greatly impressed by the investigation of his companion Engels, adopted a similar approach, which explains why so many detailed descriptions of working and living conditions can be found in Capital:

‘All the sensory organs are injured by artificially high temperatures, by the dust-laden atmosphere, by the deafening noise, not to mention the dangers to life and limb posed by closely aligned machines; dangers which, with the regularity of the seasons, produce their list of dead and wounded on the battlefield of industry. The economic use of the means of production, ripened and forced as in a greenhouse by the factory system, is transformed in the hands of capital into a systematic robbery of what is necessary for the life of the worker while at work, that is, of space, light, air, and protection from the dangerous or unhealthy concomitants of the production process; not to speak of the robbery of resources indispensable to life itself’ (Capital, Vol 1, op cit., pp. 552-553).

Marx also examined in detail food issues by considering that capitalist entrepreneurs systematically imposed undernourishment on workers. The few concessions made to the subsistence needs of the workers had no moral basis but were solely motivated by the need to obtain a higher productivity and because the situation of the labour market pushed the entrepreneurs to do so…

Today, more than 170 years after Engels’ and Marx’s workers’ inquiries, living and working conditions are sometimes strikingly similar. Whether in Latin America, Africa or Asia, hundreds of millions of people live in shanty towns without access to drinking water or public facilities. Labouring in the Maquiladoras, in the Foxconn factories in China or the cobalt mines in Africa, also bears a resemblance to the condition of the working class in 19th century England. Today, nearly 150 million children are constrained to work, a number that has been steadily increasing over the past twenty years [21]. The pandemic has only made the situation worse, adding an estimated 25 million children to the cohorts already mobilized for picking, toiling, extracting rare metal s or waste sorting. Bond labour is also expanding on global level. According to minimalist estimates, more than 70 million people are engaged around the world in forced labour in agriculture, industry and construction, not including forced marriages [22]. Finally, it should be noted that bond labour is by no means limited to the Global South but is also developing in OECD countries, particularly in tourism, catering and agricultural sectors, and even in garment sweatshops that can be found in Northern Italy or around Leicester in the UK [23] .

In the industrialized countries of the North, people may not die anymore because a mine shaft collapse or explode, but rather from a stroke or a heart attack… Death from overwork, known as Karoshi, is a phenomenon that is growing alarmingly, and not only in Japan. According to the WHO and ILO (Pega and others, 2018), overwork is estimated to cause 745,000 deaths per year globally, an increase of 20-25% from estimations made in 2005. The 6,800 deaths related to appalling working conditions on construction sites for the World Cup in Qatar demonstrate that these estimates are far from being unreal.

Real existing labour is actually getting worse, according to a large survey in 41 countries [24]. Intensive, deadline-driven or fast-paced work affects 30% of workers in the EU and almost 50% in the US, Turkey or Latin America [25]. The emotional burden of workloads is increasing in recent years, as 35-40% of respondents say, and flexibility remains a non-negotiable constraint for 40-55%. Long working weeks of 48 hours or more are imposed on an average of 20% of the workforce in the European Union; upon a quarter in the United States, and vary between 50 and 65% in countries like Turkey and South Korea. This is no surprise, but it remains a major injustice, as much as the fact that women earn significantly less than men (25 to 30% less depending on the country) while they are working more hours overall, which is also a consequence of the precariousness and informality that affects women more frequently (35 to 45% on average in the 41 countries studied). Overall, 30 to 50% of jobs are of ‘low’ or ‘very low quality’ [26] .

Exposure to physical risks is also very common. More than half of the workers or employees in many regions and countries covered by the survey are exposed to repetitive hand and arm movements, which is the most reported physical hazard. One-fifth of the employees are frequently exposed to high temperatures in the workplace.

The survey also highlights the importance of unpaid reproductive work assumed mostly by women, including in Europe. This reproductive work, including care, demands a considerable amount of time, which can vary from 20 to 40 extra hours per week on top of paid work, when children are young or pre-adolescent. For men, on the other hand, their involvement in reproductive work varies between 9 and 15 hours per week, depending on age and the number of children (Eurofound, 2019: 41).

The methodology of these international surveys is not very homogenous which mean that the robustness of results is varying from country to another. Still, this should not distract us from the fact that real existing labour coincide with a degraded social life that very often rhymes with drudgery and suffering… [27]

What is empirically true also requires theoretical and conceptual clearness. In his early writings, such as the Manuscripts of 1844, Marx focuses on Homo Faber: the human being transforms nature and the world through work/labour and transforms himself through the execution of that process. However, in his later writings, such as the Grundrisse and especially in Capital, Marx clarifies his critical understanding of labour. A first clarification was done through the distinction between abstract and concrete labour. In its concrete form, labour refers to the production of goods (and services) understood from the point of view of their use value, whereas in its abstract form, this same labour produces exchange values by submitting the concrete labouring activity to the logic of quantification and to the injunction of performance and output. The main problem is not alienation or coercion as such the ‘domination of abstract labour over concrete labour’ (Vincent, 1986; Bouquin, 2006; Postone 2011). This domination of abstract labour over concrete labour is in fact what defines wage labour, even if its intensity can vary and even if there are particularly unbearable situations and others that can be accommodated to.

By mobilizing the concept of labour-power as specific value-form of labour that is sold to the capitalist, Marx recognizes the asymmetrical and antagonistic nature of the wage relation. This social relation mobilises the worker who possesses only his/her labour-power to obtain an income and the employer holding the means of production which gives a certain capacity in organizing and controlling the execution of labour. This asymmetrical relationship is also the basis for surplus value extraction, i.e. the private appropriation of a fraction of the wealth created by living labour by the owners of the means of production [28] . This ‘economic’ relationship of exploitation also implies a socio-political dimension of ‘subsumption’ that is at the origin of the sense of alienation, the loss of control over one’s life, and not only in the workplace. These aspects, which have been extensively studied by André Gorz and other critical thinkers, became visible again, whether through the extent of burn-out phenomena or the return of a social critique of work, which is reflected in the ‘Great Resignation’, quiet quitting and the quest for meaningful autonomous activities outside the sphere of heteronomous wage labour.

In his Grundrisse as well as in Capital, Marx also refers to ‘living labour’ in opposition to ‘dead labour’, the latter meaning the labour provided by machines and automated devices. The concept of ‘living labour’ is an analytical category that refers to workers, both in their labouring activity and as human being. Living labour is thus an individual and collective ‘corpo-real’ reality that recognizes its socio-biological nature. In the capitalist system, this ‘corpo-real’ dimension is expressed primarily in a negative way: through unhealthy housing, the imperative constraint of mobility or the mutilation of daily life, not to mention the tendency towards unhealthy food that occurs more at the bottom of the social ladder and the overexposure of toxicity and pollution of certain occupations, professions or social activities. In the metropolitan areas of capitalism, and certainly in countries with a welfare state, strong trade unions and public services have made it possible to mitigate the most deleterious effects of capitalism on living conditions. The concept of ‘living labour’ therefore refers not only to the living character of labour power but also to the ‘social fabric’ that makes workers capable of labouring day after day because they have been able to reproduce this capacity to some extent.

While the concept of ‘living labour seems to be gaining some ground in France (Cukier, 2017; Harribey, 2020), in other countries like Germany, it was mobilized since quite a long time within the framework of an explicit ecological analysis. This is illustrated in particular by Oskar Negt’s work on working time and the social organisation of time as an ecological issue in itself. Indeed, for Oskar Negt, heteronomous working time is seen as antagonistic to life [29] . Defending ‘lebentige arbeit’ or living labour means taking up the cause of time of life and acting towards a drastic reduction of working time; in other words, acting in favour of an extension of control over time both on individual and collective level. Logically, the pressure to work longer and harder is inherently mortifying, whereas the will to free oneself from the obligation to work may be driven by the vital impulse of living a real life, i.e. not subjugated to working and labouring. Following this approach, we can also say that the massive and obstinate mobilisations in France against the extension of the retirement age are driven by a relative unconscious ecological aspiration of living labour.

Collective mobilisations and workers resistance, and even manifestations of misbehaviour (Ackroyd and Thompson, 2022), demonstrate that this living labour is always endowed with agency. In other words, living labour is anything but an inert mass that can be manipulated at will, but represents an active and subjective reality, that will never be completely repressed and subsumed (Barrington Moore, 1986; Ackroyd and Thompson, 2022; Bouquin, 2007). This also makes it possible to understand why living labour always remain to a certain extend reluctant, why social conflict sometimes make an unexpected comeback and remains a social condition with a latent potential for collective action (strike but not only) which remains, let us not forget, the first source of leverage for social change.

The agency of living labour is not only the expression of tensions between abstract and concrete labour, between management and employees but is fed by a fundamental contradiction between life and capital, embodied by the logic of valorisation that is imposed upon living labour. The Covid pandemic was a moment when this contradiction came back on the front stage: either life had to be privileged by bringing the economy to a halt, or profits had to be prioritized by the pursuit of economic activity at the expense of a much higher death toll. The pandemic was also a moment of existential catharsis on a mass scale, which had the effect of nourishing critical reflexivity that questions the idea of pursuing a working life that doesn’t make much sense except the fact one can lose its life in order to gain an income to live it. This ‘existential’ experience may also explain why we have seen since 2021 a disruptive return of social conflicts and a comeback of critical views upon work and labour.

To a large extent, we can say that defending living labour and decent living conditions constitutes an ecological struggle ‘in itself’[30]. Of course, it would be futile to think that greening or the ‘ecologization’ of living labour is enough to solve the ecological crisis. Indeed, everyone can easily imagine ‘ecological labour’, i.e. with high job quality and healthy working conditions, that nevertheless corresponds to an activity that is harmful to the environment. Symmetrically, one can also identify ecological activities like waste sorting or recycling in combination with non-ecological (unhealthy) working conditions for the workers involved in it. By extending the equation, we may also identify configurations where both labour and the productive activities would be ecological, was well as the opposite, where neither labour nor the productive activity would be ecological or green.

To solve this equation in a way that it is not destructive for the environment nor for the workers, it is imperative to look beyond work delivered by living labour and to integrate into the analysis the ‘dead labour’ that Marx evoked to designate capital, since this leads to directly to questioning production and the purposes that govern it. This is precisely one of Franck Fischbach’s central propositions in Après la production. Travail, nature et capital (2019): ‘What capital manages to make productive is always the result of a certain form of ‘labour’ (travail), bringing into play natural forces that go far beyond the mere human force of labour (travail)’. Indeed, labour refers not only to human involvement in the production of goods or services but also to the ‘labour of capital’, which relies on the ‘labour of nature’. As Fischbach reminds us, ‘the first characteristic of capital is its capacity to make productive for itself the widest possible range of natural forces, whether human or non-human.’ (Fischbach, 2019: 33). The second characteristic is that it cannot do so without destroying these same natural forces because ‘it cannot make natural forces productive for it without turning production into destruction and it cannot make human labour power or the naturally fertile and fruitful force of a soil productive without exhausting them. (…)’ (ibidem). The reason for this is not only located on the side of the immanent pursuit of an accumulation without limits but also in the fact that ‘the capitalist process of production, as a process of valorisation of capital, is always actualised as a process of consumption: it makes natural and social forces productive only by appropriating them, and appropriates them only by consuming and destroying them in the more or less long term.’ (ibid.).

Therefore, unconditionally defending living labour necessarily results in surpassing an economy that is under the control of capital in ‘the advent of an economy of living labour and a reasonable and democratic organisation of the common good’ (Negt, 2007: 190).

This notion of the common good and more broadly of the commons represents, in my opinion, a sufficiently open and precise intellectual and programmatic resource that allows reflection and action to be steered in the right direction. For Jean-Marie Harribey (2020): ‘Put simply, the common is what humans do together, the commons is what they have together’ (p. 262). This proposal is based on a materialist vision according to which the decision to make a ‘common good’, whether material or immaterial, is a matter of choice. The status of ‘commons’ links the object (the real substrate) to the human being who shares its use and towards the institutions that manage and preserve it. That is why commons should be kept aside of the market and the rights to access them must be guaranteed (Harribey, 2020: 11). The resources that Harribey proposes to pool in common are first water, energy, education, health and housing. But the ecological crisis demands commons to be extended to include nature and the whole earth. In order for these commons to be truly accessible to all on an equal basis, they must be excluded from private ownership and the process of valorisation and marketized exchange. Kohei Saito’s argument for degrowth communism (Saito, 2020 and 2023) goes in the same direction by considering the commons as the basis for the idea of a ‘commonisation’ of social organisation: ‘My definition of communism is therefore very simple: communism is a society based on the commons. Capitalism has destroyed the commons with primitive accumulation, the commodification of land, water and everything else. It is a system dominated by the logic of commodification. My vision of communism is the negation of the negation of the commons: we can de-commodify public transport services, public housing, whatever you want, but we can also run them in a more democratic way – not in the way of a few bureaucrats regulating and controlling everything.’[31]

6 – Concluding remarks

Faced with approaching disasters, the temptation to formulate ideological responses is great. But discussions on how to name an overall systemic alternative tend to be endless. Moreover, they can only be concluded in a practical way, when mobilisations and struggles develop on a wider level and when the urgent measures to be taken begin to take shape. Pending such developments, we will limit our remarks here to recall the main elements already stated in the course of what has preceded:

(1). The ecological crisis is human-made, global, systemic and is close to reaching a limit beyond which our planet will become uninhabitable for large parts of humanity. According to the latest projections, the time remaining to avoid a global disaster with a runaway dynamic varies between 15 and 25 years at the most;

(2). Nature does exist in a contradictory interdependent relationship with society. The same applies to society in relation to the ‘natural environment’. Moreover, we can observe a combined movement of humanisation of nature and naturalisation of humans as living beings dependent on this natural environment (biosphere, ecosphere and ecosystems);

(3). The disasters that lie ahead are rooted in fossil capitalism and the systemic imperative of profitability, which are at the root of a destructive and regressive combined re-metabolization of nature and society.

(4) The extension of the logic of valorisation upon life and reproductive labour leads to its integration into the field of social activities dominated by the market and abstract labour.

(5) Even if living labour is dominated by dead labour, capital remains dependent on the availability of living labour in order to continue to extract surplus value and to pursue the process of valorisation and accumulation. Defending ‘living labour’ is therefore an ecological struggle in itself. By reasoning this way, we articulate social and ecological struggles and integrate production and its purposes into reflection and action. The production of goods and services and its related consumption are a matter of choice: either everything is done to support and enhance the cycle of accumulation and profitability or priority is given to the satisfaction of social needs and the preservation of a common good that is a habitable and liveable earth for all.

6). To avoid disaster, it is absolutely necessary to move into the direction of an ‘emergency exit’, a post-capitalist systemic bifurcation. To reach such a goal, we must not only identify urgent measures to be taken, but also draw up a critical assessment of certain remedies that are either illusory (a technical fix like carbon capture and storage), too limited or fragmented (the carbon market), or very difficult to generalize at the present stage (prefigurative experiments) or, last but not least simply dysfunctional (so called ‘sustainable consumption’ and greenwashing).

The threat of irreparable disaster and the risk of a loss of capacity for action are real, which also raises the question of the time left over. The fatalism of the ‘collapsologists’ [32] is not only dangerous – because it feeds nihilistic or reactionary reflexes like survivalism – but it ignores the fact that time can accelerate under the impetus of a massive and global civic and social ecological mobilisation, which also explains why what takes years to happen sometimes take place in a few weeks or even days. Of course, in order to set such an acceleration in motion, humanity must manifest itself as a collective subject (actor), fighting for its common life, as a subject that defends the perpetuation of its natural conditions of existence by transforming society and its relationship with nature as much as preserving the natural conditions of life.

As Theodor W. Adorno wrote a few decades ago: ‘[It remains to be seen] whether humanity is capable of preventing catastrophe. The forms of global societal constitutions of humanity threaten its own survival, if a self-conscious global subject does not develop and intervene. The possibility of progress, of avoiding the most extreme and total disaster, has migrated to this one global subject. Everything that implies progress must crystallize around it.’ (Adorno, 2005 : 144).

Bibliography

Adorno, Theodor (2005), Critical Models. Interventions and catchwords, Columbia University Press, 448p.

Barca, Stefania (2020), Forces of Reproduction. Notes for a counter-hegemonic Anthropocene, Cambridge University press, 75p.

Barrington, Moore Jr. (1978 (2015), Injustice. The social bases of Obedience and Revolt, Routledge, 540p.

Bartoleyns, Gil (2022), Le hantement du monde. Zoonoses et pathocène, éditions du Dehors, 118p.

Batthacharya, Tithi (2017), Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentring Oppression, Pluto Press, traduit en français sous le titre Avant 8 heures, après 17 heures, Capitalisme et reproduction sociale, éd. Blast, 2020.

Benjamin, Walter (1942), Thèses sur le concept d’histoire, Payot, 208 p.

Biehl, Janet (2011), « Féminisme et écologie, un lien “naturel” ? – Résurgence d’une idée reçue, in Le Monde Diplomatique, May 2011.

BIT (2022), Forced labour, modern slavery and human trafficking « Estimations mondiales de l’esclavage moderne: travail forcé et mariage forcé – Résumé analytique ». Report https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/forced-labour/lang–fr/index.htm

BIT & Unicef Global Child Labour (2020) – Year report 2020 (on line access https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_norm/—ipec/documents/publication/wcms_800278.pdf

Bouquin, Stephen (2006), « Domination dans le travail ou domination du travail abstrait ? », in Variations, éd. Parangon, Lyon, pp. 85-99., en ligne https://doi.org/10.4000/variations.509

Bouquin, Stephen (coord.) (2007), Les Résistances au travail, Syllepse (épuisé), 378p.

Bouquin, Stephen (2019), « La défense du “travail vivant” est un combat écologique en soi », in La Lettre du CPN n°5, juin 2019, p. 4-6.

Brohm, Jean-Marie (2003), Les principes de la dialectique, éd. La Passion, 254 p.

Cravatte, Julien, L’effondrement, parlons-en. Les limites de la collapsologie, 2019, 48p. Miméo, https://www.barricade.be/sites/default/files/publications/pdf/2019_etude_l-effondrement-parlons-en_1.pdf

D’Eaubonne, Françoise (1974), Le féminisme ou la mort (Éd. P. Horay), 251 p .

Descola Philippe (1986), La Nature domestique : symbolisme et praxis dans l’écologie des Achuar, publication par la Fondation Singer-Polignac, Paris : éd. de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 1986, 512 p.

Descola, Philippe (1994). In the society of nature: a native ecology in Amazonia. Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology 93. Nora Scott (trans.). Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Descola, Philippe (1996). The spears of twilight: life and death in the Amazon jungle. Janet Lloyd (trans.). New York: New Press.

Descola, Philippe (2005; [2013]. Beyond Nature and Culture. Janet Lloyd (trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Descola, Philippe (2005), Par-delà nature et culture, Paris, Gallimard, coll. « Bibliothèque des sciences humaines » 640 p.]

Descola, Philippe (2010), Diversité des natures, diversité des cultures, Paris, Bayard, 84 p.

Descola, Philippe (2010), L’Écologie des autres. L’anthropologie et la question de la nature, Paris, éditions Quae, 112p.

Engels, Friedrich (1939), Lettres de Wuppertal, disponible en anglais https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1839/03/telegraph.htm

Engels, Friedrich (1945), La situation de la classe laborieuse en Angleterre, préface de Eric Hobsbawn. En ligne https://www.marxists.org/francais/engels/works/1845/03/fe_18450315.htm

Engels, Friedrich (1884), L’origine de la famille, de la propriété privée et de l’Etat (online https://www.marxists.org/francais/engels/works/1884/00/fe18840000.htm )

Eurofound & ILO (2019), Working conditions in Global perspective ; report https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef18066en.pdf

Fischbach, Franck (2019), Après la production. Travail nature et capital, Vrin, Paris, 190 p.

Foster, John Bellamy (1999), « Marx’s Theory of Metabolic Rift: Classical Foundations for Environmental Sociology », in American Journal of Sociology 105 (2), 366-405, 1999.

Foster, John Bellamy (2000), Marx’s Ecology: Materialism and Nature, New York: Monthly Review Press.

Foster, John Bellamy; Clark, Brett; York, Richard (2010), The Ecological Rift: Capitalism’s War on the Earth, New York: Monthly Review Press, 2010), 544 p.

François, Stéphane (2022), Vert-Bruns. L’écologie de l’extrême droite française, éd. Bord de l’eau.

Gardey, Delphine (2005), « La part de l’ombre ou celles lumières ? Les sciences et la recherche au risque du genre », in Travail, Genre et Sociétés, n°14, p. 29-47.

Gardey, Delphine et Löwy, Ilana (dir.) (2002), L’Invention du naturel. Les sciences et la fabrication du féminin et du masculin, Éd. Archives contemporaines, Paris, 227 p.

Gorz, André (1978), Ecologie et politique, Galilée, qui ajoute le texte «Écologie et liberté » paru en 1977

Gorz, André (1988), Métamorphoses du travail, quête du sens, Gallimard.

Graeber D., Wengrow D. (2021), The dawn of everything. A new history of humanity, Penguin Books, London, 720p. [Graeber, David, Wengrow David, (2021), Au commencement était … Une nouvelle histoire de l’humanité, éd. Les Liens qui Libèrent, 752 p.]

Guillibert, Paul (2021), Terre et capital. Pour un communisme du vivant, éd. Amsterdam, 244p.

Harribey, (2017), « La centralité du travail vivant », online https://france.attac.org/nos-publications/les-possibles/numero-14-ete-2017/dossier-le-travail/article/la-centralite-du-travail-vivant

Harribey, Jean-Marie (2020), Le trou noir du capitalisme. Pour ne pas y être aspiré, réhabiliter le travail, instituer les communs et socialiser la monnaie, Le Bord de l’eau, 2020, 336 p.

Harvey, David (2015), Seventeen contradictions and the end of Capitalism, Profile Books, 338p.

Lallement, Michel (2022). L’école durkheimienne et la question des femmes, in Lechevalier Arnaud, Mercat-Bruns Marie, Ricciardi Ferruccio. Les catégories dans leur genre. Genèses, enjeux, productions, Teseo Press, pp.63-89.

Larrère, Catherine (2011), « La question de l’écologie ou la querelle des naturalismes », Cahiers philosophiques, vol. 127, no. 4, 2011, pp. 63-79.

Latour, Bruno (1993), We have never been modern, Harvard University Press, 168o. [Latour B. (1991), Nous n’avons jamais été modernes. Essai d’anthropologie symétrique, Paris, La Découverte, 210 p.]

Latour, Bruno (2004), Politiques de la nature. Comment faire entrer les sciences en démocratie, Paris, La Découverte, 392p.

Latour, Bruno (2015), Face à Gaïa. Huit conférences sur le Nouveau Régime Climatique, éd. La Découverte, 400 p.

Latour, Bruno et Schultz, Nikolaj (2022), Mémo sur la nouvelle classe écologique. Comment faire émerger une classe écologique consciente et fière d’elle-même, éd. La Découverte.

Latour, Bruno et Woolgar, Steve (1986)], The laboratory life. The construction of scientific facts, Princeton university press, 296p. [La Vie de laboratoire. La Production des faits scientifiques, Paris, La Découverte, 308p.]

Lossin, R. H. (2020), « Neoliberalism for Polite Company: Bruno Latour’s Pseudo-Materialist Coup », juin 2020, in Salvage #7, journal en ligne https://salvage.zone https://salvage.zone/neoliberalism-for-polite-company-bruno-latours-pseudo-materialist-coup/

Löwy, Michael (2016), « Walter Benjamin, précurseur de l’éco-socialisme », Cahiers d’Histoire. Revue d’histoire critique, 130, 33-39.

Malm, Andreas (2017), L’Anthropocène contre l’histoire. Le réchauffement climatique à l’ère du capital, La Fabrique, Paris, 242 p.

Malm, Andreas (2016), The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming, Verso Books, 496 p.

Malm, Andreas (2020), Corona, Climate, Chronic Emergency. War Communism in the Twenty-First Century, Verso Books, 224 p.

Marx, Karl., Le Capital. Critique de l’économie politique. Livre premier. Le développement de la production capitaliste. III° section: la production de la plus-value absolue. Chapitre X : La journée de travail.

Marx Karl (1974), Le Capital, Livre troisième – Le procès d’ensemble de la production capitaliste, Paris, éd. sociales.

Marx, Karl (1996), Critique du programme Gotha (du parti ouvrier), Paris, éd. Sociales.

Meissonier, Régis (2022), “Roy Bhaskar. Le réalisme critique britannique”, in Yves-Frédéric Livian éd., Les grands auteurs aux frontières du management (pp. 147-156). Caen: EMS Editions.

Merchant, Carolyn (1980), The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, San Francisco, 1980 (2ème éd. 1990); traduction française par Margot Lauwers: La Mort de la nature : les femmes, l’écologie et la Révolution scientifique, Marseille, Wild project, 2021.

Merchant, Carolyn (1980), The Death of Nature (La mort de la nature, 2021 pour l’édition française)

Mies, Maria (1998 (1986)), Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. Palgrave MacMillan, 251 p.

Moore, Jason W. (2000), “Environmental Crises and the Metabolic Rift in World-Historical Perspective”, in Organization & Environment, 13(2), pp. 152-157.

Moore, Jason W. (2011), Transcending the metabolic rift: a theory of crises in the capitalist world-ecology, The Journal of Peasant Studies, 38:1, 1-46, DOI: 10.1080/03066150.2010.538579

Moore, Jason W. (ed.) (2016), Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, PM Press/Kairos.

Mutambudzi, Miriam (2021), « Occupation and risk of severe COVID-19: prospective cohort study of 120 075 UK Biobank participants, » in Occupational and Environmental Medicin. DOI: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106731

Negt, Oskar (2001), Arbeit und menschliche wurde, Steidl, 747 p.

Neumann (Alexander), Après Habermas. La Théorie critique n’a pas dit son dernier mot, éditions Delga (philosophie), Paris, 2015, 210 p.

Neumann, Alexander (2007), « Negt et le courant chaud de la Théorie critique : Espace public oppositionnel, subjectivité rebelle, travail vivant », in Negt Oskar (2007), L’espace public oppositionnel).

Neumann, Alexander (2010), Kritische Arbeitssoziologie (Les sociologies critiques du travail), éditions Schmetterling, Stuttgart, 2016 (seconde édition), 200p.

Okafor-Yarwood Ifesinachi & Adewumi Ibukun Jacob (2020), Toxic waste dumping in the Global South as a form of environmental racism: Evidence from the Gulf of Guinea, in African Studies, 79:3, 285-304, DOI: 10.1080/00020184.2020.1827947

Pega, Frank e.a. (2021), “Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries. 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury”, in Environment International, Volume 154, 2021.

Plumwood, Valerie (2012), The Eye of the Crocodile, edited by Lorraine Shannon. Canberra: Australian National University E Press 99p.

Postone, M. (2011). “Quelle valeur a le travail ?”, in Mouvements, 68, 59-69. https://doi.org/10.3917/mouv.068.0059

Sahlins, Marshall (1962), Moala: Culture and Nature on a Fijian Island. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Sahlins, Marshall (1972), Stone Age Economics, New York, de Gruyter Press, 1972.

Sahlins, Marshall (2008), The Western Illusion of Human Nature. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Sato, Kohei (2023), Marx in the Anthropocene, Cambrigde University press, 276p.

Servigne Pablo & Stevens Raphaël (2015), Comment tout peut s’effondrer, Petit manuel de collapsologie à l’usage des générations présentes, Paris, 304p.

Tanuro, Daniel ((2014), Green capitalism. Why it can’t work (French L’Impossible capitalisme vert, 2010. La Découverte, 289p.

Tanuro, Daniel (2020), Trop tard pour être pessimistes. Eco-socialisme ou effondrement, éd. Textuel, Paris, 324p.

Thompson, Paul & Ackroyd, Stephen (2022), Organisational misbehaviour, London, 389p.

Vincent, Jean-Marie (1987 (2019), Critique du travail. Le faire et l’agir, éd. Critiques, 288p.

Wallace, Robert (2016), Big Farms Make Big Flu. Dispatches on Influenza, Agribusiness, and the Nature of Science, Monthly Review Press, 400p.

Walvin, James (2019), How Sugar Corrupted the World. From Slavery to Obesity, Robinson, 352p. [French: Histoire du sucre, histoire du monde., La Découverte, 2020, 322p.]

Footnotes

[1]. Michael Löwy, « Walter Benjamin, précurseur de l’éco-socialisme », Cahiers d’histoire. Revue d’Histoire Critique, 130 | 2016, 33-39.

[2]. Haeckel goes on to explain that existence is determined by the inorganic nature to which each organism must submit, i.e. the physical and chemical characteristics of the habitat, the climate, the biochemical characteristics, the quality of the water, the nature of the soil, etc. Under the name of conditions of existence, we understand the whole of the relations of organisms with each other, either favourable or unfavourable.

[3]. The survival of the fittest as a biological principle applied to humans comes from Hubert Spencer, who extended Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution to the societal scale. Pierre Kropotkin strongly relativised the relevance of Darwin’s theory of evolution applied to humans and defended an approach of humans as social and collective beings whose survival depends on mutual help, which marked their evolution by favouring the development of communication and language.

[4]. See Antoine Dubiau (2022)

[5]. One can doubt the relevance of the notion of ‘crisis’ when it becomes structural, but it keeps all its meaning according to a pragmatic definition (‘sudden event or long evolution which reveals structural weaknesses, inherent to a system’) which is less the case according to a lexical definition (‘set of pathological phenomena manifesting themselves in a sudden and intense way during a limited period)

[6]. As a reminder, the massive disruptive rains of the summer of 2022 caused landslides and mud torrents in Pakistan, destroying the homes of 7 million people and killing over 50,000.

[7]. For a general overview published on a official EU platforms, see the statements made by prof. Georgina Mace, head of the Centre for Biodiversity and Environmental Research, London University, https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/sixth-mass-extinction-could-destroy-life-we-know-it-biodiversity-expert

[8]. The racialization of humanity refers to a biological division of human beings. Based on scientific claims, it considered certain human populations as inferior or incapable of accessing civilization. The essential thing is, of course, to continue to recognize that gender, race and class are above all social and political constructions.

[9]. See the interview with Philippe Descola, https://reporterre.net/Philippe-Descola-La-nature-ca-n-existe-pas From his in-depth study of the Jivaros of Amazonia, Descola deduces that there are several ways of inhabiting the earth and relating to the so-called natural environment. When the Jivaro Indians anthropize the Amazonian rain forest on a symbolic as well as a practical level, they do so by seeking to preserve a homeostatic balance (biodiversity, variety of fauna and flora) (Descola, 1986).

[10] R.H. Lossin (2020), ’Neoliberalism for polite company. Bruno Latours pseudo-materialist coup’, in Salvage n°7 Towards the proletarocene, Online https://salvage.zone/neoliberalism-for-polite-company-bruno-latours-pseudo-materialist-coup/