1 – Introduction

In the 1950s, French sociology of work and labour relations distinguished itself from North-American social psychology by recognising the conflicting dimension of work and the emancipatory stakes this could contain. From the 1980s onwards, sociological analyses focused more on social interactions, and above all on the internalisation by employees of the logic of performance and management standards. It is also during this last period, from 1990 to 2010, that the issue of domination emerged, favouring an analytical grid where employees have ceased to oppose management.

During my doctoral studies, and throughout my research activities of the last two decades, I favoured an approach that continued to integrates conflict and resistance into the analysis of work and labour. This is as much a theoretical choice as it was and remained an empirical observation. Such a conceptualisation of work and labour does not consider conflict as an ‘anomaly’ but recognises the antagonistic nature of labour relations at the very core of them. From there on, I took a position in some sociological controversies regarding work, labour and its ongoing transformations by asserting that these are at least partially determined by the need for management to increase or to maintain the level of surplus extraction as well as resistance and oppositional behaviour by labour.

Certainly, the wage relationship contains several types of conflicts. Competition between employees can be characterised as a kind of ‘horizontal’ conflict that can take on many faces, ranging from competition for favours, disassociation, harassment or some kind of inter-statutory and intergenerational conflicts. Still, there is always also, even in a minimal way, a ‘vertical’ conflict which opposes the workforce to the management and the employer. This conflict is not only fuelled by issues of power, as pointed out by Michel Crozier and Alain Touraine[2], but also by a conflict of interests concerning the partition of surplus value and the monetary and symbolic recognition of the effort made.

At the origin of my approach, a disagreement can be found with a conceptualisation of work that limits the definition of it to the exercise of a constraining activity, or an expenditure (skilled or not) of energy surrounded by exchanges of information. Such an approach limits the sociological analysis to the concrete way it’s being carried out, to gestures and postures and to symbolic interactions within the workplace. These aspects are important, but they tend to leave aside structuring dimensions such as inequalities of power, the division of labour as well as the impact of wage labour, both at the domestic level and at the level of the public space (labour market and normative regulations). The aspect of pay, or work-effort bargaining is an aspect that is quite often disregarded or even neglected by French sociology of work. Apart from the institutional separation of academic disciplines such as sociology and political economy, another more silent explanation can be found in the strong Proudhonist tradition – and the concomitant marginal Marxist traditions – that can be found among scholars as well as trade unionists. The fact that paid work or labour is not limited to the execution of tasks, that it does not exist in itself, but is carried out against the background of a social relationship of exploitation[3], under control of management is not quite often acknowledged. The fact that this reality will affect social behaviour as well as the relationship to work that people tend to adopt even less. A sound analysis of wage labour implies integrating the existence of the employer, the company, and management as well as recognising that the constrained act of working involves surplus extraction which will be embodied in a higher workload and / or a partial or false recognition of one’s contribution and commitment.

In other words, wage labour remains based on an antagonistic social relationship in which employers cannot fail to try to maximise profits by making people work more for the same wage, or by reducing the latter in relation to the work done (productivity increases). At the same time, wage workers cannot refrain themselves to try to be better paid for their efforts or ask to be better paid on the basis of increased efforts. Insisting on this aspect should not make us forget that this social relationship is also asymmetrical and that it therefore implies a ‘subsumption’– a term I prefer to that of ‘domination’ – whose faces can vary enormously, ranging from factory despotism based on coercion and repression to ‘controlled autonomy’ through targets, performance, strong work ethos, the occupational culture of corporate chauvinism.

To put it differently, when we understand wage labour as a social relationship, we have to do so from two opposite viewpoints, both that of the employees and that of the employers. From this double viewpoint, the observation that there is no ‘truce in sight’ is even truer. Almost all managerial reorganisations can be understood as acts promoting more effort on the part of ‘living labour’, more creativity and commitment, in view of stagnant or slightly increasing pay, in view of the efforts made.

This critique, which can be identified as Marxian, extends the analysis of André Gorz[4], from when he considered wage labour as a heteronymous reality, or elaborated by Jean-Marie Vincent[5] when he recalled the extent to which real subsumption always nourishes oppositions and a critique of work. The reality of ‘domination’, so often evoked in sociological literature, refers basically to the domination of abstract labour over concrete labour, which does not mean this domination is ever completed, definitive nor absolute. Firstly, because it is not insensitive to the balance of power between employers and trade unions (when the latter are present), neither to the legal-administrative frameworks of industrial relations (particularly the right to strike), as well as it involves both bodies and minds mobilised during working time. Faced with various intensities of psychological sufferingor or the resentment of not being sufficiently recognised for one’s contribution, sooner or later employees may lose their credulity towards management and slide into various kinds of opposition. We could also mention Oscar Negt [6], member of the Frankfurt Institute for Social Research, who remobilised Marx and the concept of ‘living labour’ (lebentige arbeit) to emphasise the extent to which this ‘living’ nature of the workforce, in opposition with the ‘death labour’ (tote arbeit, i.e. capital), implies also a permanent uncertainty towards the concrete course of the labour process. Other works, quite often ignored by French labour sociologists, such as those of Cornelius Castoriadis [7], could also be cited. Apart form his early writings as member of the journal Socialisme ou Barbarie and political group, Castoriadis is characteristic for an analysis articulating social relations of production with state and the development of civil society institutions, considering the pacification of work and labour as harder to achieve than it is the case on the level of a political regime.

A whole series of research investigations confirm the approach of work situations as incessantly conflicting, even without necessarily adopting a Marxian conceptualisation. One example is the historian Alf Lüdtke [8], who studied work behaviour in the context of the Nazi regime in the nineteen thirties finding traces of ‘rebellious subjectivity’ through shopfloor reports from hierarchical superiors, sanction vouchers and testimonies of middle management. These traces revealed that a productive activity was accompanied by a permanence of oppositional behaviours, even after the elimination of trade union presence. Following Alf Lütdke, this kind of conduct can be identified as Eigensinn which he defined as a kind of silent but stubborn oppositional attitude – such as ‘I tend do only doing what I want to do’ – expressing also a kind of undisciplined individualism.

2 – The blind spot of French sociology of work

The publication of a collective reader Résistances au travail in 2008 [9] was an opportunity to reopen the discussion on how ‘atmosphere at work’ did evolve the last decade. The expression of ‘athmospère’ or ambiance was used by the labour historian Nicolas Hatzfeld when he referred to shopfloor situations marked by informal behaviour [10]. Being himself a former ‘établi’ –political activists choosing to work in factories as ordinary workers in order to be among ordinary working people – he tended to acknowledge variations of work commitment that were mots of the time intentional. Others such as Jean-Pierre Durand [11] after having elaborated a typology of wage relationship configurations in the automotive industry focussed research upon consent and ‘voluntary servitude’ – a notion borrowed from Gustave de la Boëtie – considering the workplace as pacified since the unions lost all bargaining power, the workers fear to lose their jobs and most of them are subjugated by the hegemonic ideology of effectiveness. Danièle Linhart, in a quite same way, emphasised the disappearance of the ‘collective worker’ in the face of omnipotent management[12]. In addition to this, there was the idea, defended in particular by Stéphane Beaud and Michel Pialoux, that workers wanted to be considered as technicians or operatives but certainly not as members of the working class. It should be noted that the mainstream definition of the ‘classe ouvrière’ is quite restrictive and limit the class boundaries to blue collar workers, to productive labour (in opposition to unproductive labour in services sector) which concern only a section of the labouring class if we apply a larger definition of the labouring class [13].

The new forms of work organisation imported from Japan in the 1990s, such as team work, Kaizen or Kanban, certainly succeeded to obtain greater involvement of work groups and to guarantee better quality[14]. These new forms of organisation aimed to obtain from workers a degree of implication in correspondence with demanding standards of lean management and the ongoing juts-in-time flow of production. This had to be done through the mobilisation of informal resources and tacit knowledge in order to increase productivity. However, by the end of the 1990s, productivity gains were also obtained through intensification and other elements of degrading of working conditions (health and safety), which resulted in a minimalist and consequently worn-out workforce. In some cases, this translated itself into a return of open social conflict, while in others, opposition remained invisible. A detailed analysis of the emergence and spread of lean production in the automotive industry (such as Bouquin, 2006) shows how and why it has become a hegemonic model.

It is true that, like Taylorism, there are many variants of this new ‘one best way’, but the fundamentals can be identified quite easily: cutting costs at all levels, not only of labour but also regarding capital (investment), intensification of work and extension of the use of technical installations, recurrent evaluation of oneself and colleagues; versatility and reduction of stocks and immobilised capital; segmentation of workforce according to status and imposition of team (or project) work; fragmentation of the labour process through subcontracting and the introduction of business units acting like small firm supplying to each other[15]. In the end, while lean management certainly led to increases in productivity, it can also be said it acted as a source of wasting human energy, just as it can give way to quality losses, serial defects and ruptures in the labour process [16].

However, the main sociological analysis in France asserted that workers where defeated, collective workers was atomised and has chosen to reconcile themself with work and management. Contrary to this interpretation, I maintained the opposite: firstly, that there was no definitive pacification possible, secondly, that in some productive spaces, open conflicts (strikes) where still present even if the bargaining power of unions was losing ground; thirdly, that oppositional practices and behaviours at the shopfloor level demonstrate both the necessity for employees to cope with the situation as well as their unwillingness to consider this situation as ‘fair enough’ [17].

The sociological study of work settings, factories or shopfloors should not only look at (apparently) pacified situations but also integrate atypical cases which contradict the thesis of pacification, as I was able to do on the basis of case studies about the Renault Trucks assembly plant in Caen, the factories of Chausson (specialised in vans and camping cars) in Parisian suburbs and in Picardy or the Volkswagen-Audi assembly plant in Belgium (Brussels).

Following the hypothesis that the way employees realise their work tasks not necessarily match their opinions, I started to look after traces of critical reflexivity about work[18]. Even in the late nineties, one could already find such traces in surveys. Let us mention, for example, the survey done by Christian Baudelot and Michel Gollac[19] at the end of the 1990s showing that 74% of white-collar employees had ‘the feeling that they were being exploited’, much more than the 45% blue-collar workers thought. It should be noted that these beliefs appeared in combination with the feeling of being treated unfairly and basically express the expectation for professional recognition that management refuse to honour. Of course, these opinions do not necessarily question the social order of capitalism as such, but that is not really the point. Indeed, let us not forget that such a critique occurs most of the time during exceptional and relatively short periods, such as before or during social upheavals or general strikes such as the ones of 1936 and 1968 in France.

Given the fact that work settings and labour relations are much more heterogeneous than one might suppose, it is essential to analyse the labour process as far from pacified and normalised. In reality, the approaches centred upon domination do suffer from a double flaw. The first flaw is heuristic or empirical. Very often, they neglect social behaviour and opinions that do not consent to managerial domination, under the pretext of their great marginality. However, what exists now has not always been and will not necessarily be the case in the future. Unless we affirm that nothing has ever changed and will never change, sociology must also seek to integrate contradictory trends unfolding and recognize that any present situation contains a range of possible futures. The second flaw is both theoretical and ethical. Through publications, lectures at the university and debates in the public arena, sociology had always a public character, which means that sociologists should acknowledge that their narratives also structure representations of social reality. When sociological analysis is reducing actors to consent and ‘voluntary servitude’, this may end up in the reproduction of a discourse – wrapped or not in an academic format – that contribute to deprive actors of their capacity for action. Even if the performative effect of sociological narratives is reduced, in France, they find audience among trade union activists, who are looking after explanations for their lack of effectiveness. With some help of structural-functionalist sociology, the explanation is ready-made: collective action is doomed to be ineffective because the employees do not want it, since they have internalised the performance injunctions and adhere to management. Paradoxically, where the sociological reflexivity which was called by Pierre Bourdieu should allow for a better understanding of social reality, it ends up proclaiming the status quo as unsurpassable, which has never been the case anyway.

Broadening the field of analysis nevertheless requires precautions. Following Jean-Claude Passeron in Le Raisonnement sociologique[20], the first pitfall of an approach aimed at restoring some kind of heuristic justice is to substitute ‘populism’ for ‘miserabilism’. In other words, to project wishes and expectations onto the conduct of actors, where miserabilism expresses the disappointment of these expectations on the part of the researcher. It is therefore necessary to take all methodological precautions and to avoid hasty theorisations. But to me, the basic premise remains, namely not to ‘freeze’ a social situation by locking actors into behaviours not all of them had or will have, and by qualifying their opinions as manufactured and alienated. That is why I kept up to a certain amount of caution in the analysis of the social behaviours grouped together under ‘resistance au travail’ defined in the following way:

“Resistance is certainly ambivalent and coexists with practices that allow for adjustment, adaptation and (partial) reappropriation of work situations. However, they differ from the latter since they express latent and informal forms of dissent, opposition, of refusal to conform or to comply. Resistance at work refers to behaviour that is to a certain extent disruptive and intolerable for those who supervise, employ and put others to work”[21].

Other sociologists in France favour a very specific restrictive definition of ‘resistance’, which corresponds to intentional and open ‘sedition’ towards management and work. The limit of such a definition is that it has almost no heuristic value[22]. Searching after resistance as a ‘partisan sedition’ does not make much sense when we know how many employees – even well-off –are indebted and how many depend on their present job, especially in times of unemployment, precariousness and difficult labour market mobility. But, let us remember how much in periods of full employment in France, most firms faced a 30-50% turnover, while this did not prevent strikes at all, some of which took place without the support of trade unions[23]. Gradually, the economic crisis of the nineteen seventies and eighties led to the reconstitution of a ‘reserve army’ of labour, which forms a coercive and disciplinary social context, to which has been added a series of workfarist reforms regarding the welfare system, reducing both the amount and duration of unemployment benefits. In such a context, searching after resistance as ‘partisan sedition’ means expecting behaviour that in reality corresponds to social suicide. To put it bluntly, adopting such a definition makes of resistance a kind of strawman…

Despite all of this, the controversy is all but over. How should sociologists analyse social behaviour corresponding to ‘exit’? How many professionals, white collar employees around the age of 45 start to look after a way out of their job, in the form of a ‘second career’, a better work-life balance, notably through the choice to refuse promotion and the acceptance of a ‘dead-end’ job. How many young temp workers, even being confronted with precarity, do not really engage in the way that they are expected to do, i.e., engage in a harsh competition for some scarce positions? [24] Others are happy to be able to leave the company at 55 thanks to early retirement. We can identify all kinds of conduct corresponding to ‘high end’– exit such as becoming a farmer, a cooperative entrepreneur or a self-employed person. Such behaviour may be the contrary of (internal) opposition and resistance but there is still a link between them, namely the degree of dissatisfaction regarding tasks, targets, managerial standards or a general work climate.

A broader definition of resistance refers not only to the persistence of informal behaviours such as braking, loitering, wigging and sometimes sabotage, but also to the existence of oppositional or critical spirit regarding work and to integrate this into a broader set of conduct by which employees try to re-appropriate, even if only partially, their work situation; if not to loosen the stranglehold of the logic of performance. In fact, resistance to work is often blurred and mixed with adjustment or accommodation behaviours.

Why should this broader definition be prioritised? Because human work is a ‘living matter’ characterised by great plasticity and by its reflexive nature. Acting at work is therefore never a case of complete ‘domination’ and, even if it seems to be, we cannot exclude the hypothesis that employees mimic their servitude and pretend to fully ‘play the game’. Still, this game implies margins of freedom, as has been shown by a number of studies in the 1970s and 1980s on the difference between ‘prescribed work’ and ‘real work’[25]. It is true that information technologies and the injunction of new work ethics have changed the situation, but without moving beyond subsumption, quite the contrary…

For Michael Burawoy[26] who’s analysis on shopfloor behaviour carried him very close to Pierre Bourdieu’s theoretical analysis about the ‘double nature of work’. Following Burawoy, production games represent a kind of alienated behaviour that leads the individual to deliberately participate to his own exploitation. Burawoy analysis of production games became quite popular among French sociologists after the publication of some large extracts in the journal Actes de la Recherche en Sciences Sociales[27]. For many years, Buwavoy’s account was taken for granted in French sociology and served as demonstration on how uncontested management has become and how successful alienation could be. Still, Burawoy overlooked the importance of financial gains the production games could offer, sometimes even by 30%. This aspect was already highlighted by Donald Roy who conducted a similar survey twenty years earlier in exactly the same company. When production games integrate a wage-effort bargaining to such an extent, it can hardly be considered as being outside the productive relation between labour and capital, as was recalled by Paul Thompson and Pierre Desmarez in two classical works on the sociology of work [28].

In reality, those games do not express the will to collaborate actively to one’s own exploitation in the Marxian sense of the term, but an attempt to reduce the degree of exploitation by seeking to be paid as much as possible for a constant or reduced effort. Indeed, wage labour remains a relationship where the work performance is exchanged for a pay, which implies on the side of the employee the possibility of ‘pulling on the rope’ or ‘tugging at the heartstrings’… The production games are not reducible to ‘false consciousness’ since they also express a workshop culture based on cooperation between workers, which allowed the ‘collective worker’ to exist socially and to assert its social existence from a management viewpoint.

Our own sociological research included the study of collective action frameworks and trade unions practices on the shop-floor level. A comparative analysis helped me to take into account the various realities of labour relations in big and small firms, as well as the variations determined by the strength of trade unions sometimes renewed by counter-power practices at organisational level. While remaining cautious and recognising the existence of very different situations, depending on the size of the company and the profile of the trade union teams, the fact is that one can still encounter situations similar to what Jean-Daniel Reynaud has called ‘combined regulation’ which can be understood as collective bargaining with some concessions by employers[29].

Of course, when social conflict is less present and trade union action is no longer able to improve working conditions, it is certain that the ‘collective worker’ become more vulnerable which will push individuals to find other ways of coping with the situation. Informal groups can take over and different kinds of conflicts develop, more interpersonal, informal and most of the times confidential. Certainly, management has the power to counteract upon these, by mobilizing surveillance technologies, by repressing recalcitrant spirits ; by promoting docile employees, management gives itself the means to influence the conduct of workers. At the same time, the productive demand for quality cannot be obtained solely by coercion. It also requires loyalty and commitment, which opens up certain margins for negotiation. Managerial practices take this into account and combine intensive mobilisation of ‘human resources’ and high turnover. Core workers are given more and better working conditions, work is less hard while temp or peripheral employees are submitted to high pressure and a performance that is obtained by the promise of a better contract and recruitment among the stable employees. A high turnover makes it possible to externalize the social and human effects of this wear and tear at work. This is illustrated by the high turnover in fast-food restaurants, call centres and logistics. Similarly, the segmentation of the workforce – with a flexible section approaching 30% in many many situations in France – makes it possible to discipline behaviour at work and to reduce open conflicts such as strikes. For insiders, loyalty is obtained in exchange for a certain amount of job security and better work conditions; for peripheral employees, temp workers, commitment is obtained through the promise of future stabilisation, using the status of insider as a perspective for the outsider.

In the tradition of labour process theory, resistance and misbehaviour has been the subject of much interpretations[30]. Following Paul Thompson[31], one of the leading sociologists on this issue, organisational misbehaviour certainly has various origins such as the refusal of work intensification, being underpaid, resentment linked to non-promotion or unappreciated conduct of management. And indeed, if we reason in this way, resistance towards and at work cannot be dissociated from labour relations in a capitalist environment. The following diagram based upon Ackroyd and Thompson (1999) shows how resistance to work can be articulated to the relationship to work as well as other aspects of labour relationship.

Figure 1 – Dimensions of social behavior at work / regarding work

|

Appropriation of time |

Appropriation of work |

Appropriation of production |

Appropriation of identity |

| (Loyalty) |

self-acceleration |

Self-control of labour process |

Self-organisation |

Identification to targets |

| EngagmentMotivation |

Acceptance of the rate |

Normal execution of tasks |

Working on a fast lane |

Rituals of

desocialisation |

| Conditional Cooperation |

Putting the brake on the rate |

Negociate the rate (freinage) |

Output restriction |

Local work cultures in office and shopfloor. |

| (Voice) |

Mastering working time (refusing overtime) |

Revendications |

Workers control |

Games, recreational or sexual activities |

| Retrait |

Strolling and braking |

Minimalism service |

‘Perruque’ (wigging) |

Indifference |

| Denial |

Wasting one’s time |

Retention of quality |

Larceny |

Playing the fool |

| Hostility |

Absence |

Destruction and sabotage |

Fraud |

Group or class solidarity |

| (Exit) |

Turnover |

Looking after another job / position |

Theft |

Rejection of the company, or the brand |

Published in Bouquin (2008) and based upon Ackroyd & Thompson (1999)

How should this diagram be read? First of all, it is important to recognise the vast variety of work conduct that can hardly be understood as stable and unequivocal. The relationship towards labour and work is never solely instrumental (financial) nor expressive (self-fulfilment and joy), but combines several aspects which may be mixed or under tension. This relation towards labour also evolves according to the concrete experience of the working day, of age and seniority. It will also be underpinned by expectations in terms of recognition, career development and better working conditions that may or may not be met. Employees are not insensitive tools and consequently, they can slide from consent to resistance. The fact that the latter category will be a minority does not change anything from a scientific point of view since informal autonomous and resistant behaviour remain present and pay fuel social space. In saying this, I am also questioning a sociological approach that limits itself to what is apparent and refuses to acknowledge that certain practices will remain quite invisible. Finally, this diagram highlights the fact that it is important to study dynamics that allow social groups to continue to exist in the face of management, as well as the reasons that may lead some individuals to opt for recalcitrant or the opposite, docile behaviour.

Before concluding this section, I would like to make some critical remarks about two approaches that differ from my own. The first, developed by Daniel Bachet [32], criticises the tendency to reduce social interactions in the firm to power games, which feeds into, following him, the illusion of a capacity to influence labour relations on the basis of micro-resistances.

“It seems that one of the problems of a certain sociology of work is that it has not always succeeded in reconstructing the mechanisms of interdependence which unite labour relations and the more strategic rules of action structuring the economic and social game within and outside the company. There is therefore a great risk of reducing the analysis of conduct at work to ‘power games’ and forms of opposition that are somewhat disconnected from the broader fields that guide the actions of agents.”

For Bachet, ‘transgressions’ or deviant conduct do not change anything and cannot replace a collective action that defends different criteria of management and accountancy such as a fair partition of added value (surplus value) through wage increases or reduction of working time. Of course, it is true oppositional behaviours ‘don’t change anything’ fundamentally at the level of the capitalist social order but at the same time, it is absolutely wrong to consider them as ‘functional’.

To demonstrate this, we can take a closer view upon ‘wigging’ or la perruque as it is analysed by Robert Kosmann who was a former skilled worker at Renault and militant CGT trade unionist during almost three decades. Far from being a sort of ‘safety valve’, they participate, following Robert Kosmann [33], in maintaining links between members of the ‘collective worker’ and to mobilise this quite vague social entity along lines of cleavage that converge with labour and capital antagonism. In his book, Kosmann collected many proofs of ‘wigging’ or la ‘pérruque’ with workers working for themselves. For sure, ‘wigging’ challenges the legitimacy of the employer’s power to have complete disposability of tools and working time. Its practice represents the refusal of alienation and the mobilisation of professional skills for the sole purpose of the operational result. Robert Kosmann considers also that ‘wigging’ is first of all the expression of professional skills that are inseparable from a professional aesthetic and the will not to sell them out to the employer[34].

Rather than considering all types of employee resistance as futile, or even functional, as did Bachet, it seems more judicious to us to understand its presence in relation to unions, their weakness, as a sort of consequence of a ‘deficit’ in collective bargaining power, which, without remedying to this problem, will lead to a ‘productivity deficit’. Following this path, we can also consider that empowerment of trade unions and rebuilding the capacity for collective action imply the recognition of critique of work as it is expressed among workers. Secondly, resistance should also be understood as expression of a shared culture and ethics about work, about the fact being employed as a worker and often misrecognised.

If management wants to make more sense of working, in order to obtain a reconciliation with constrained action and sufficient productivity, it will have to use the carrot as much as the stick. In other words, although resistance towards work does not open up a horizon for transforming the capitalist social order – which was never pretended to be the case – it may also contribute to maintain a collective spirit, a work-culture and even lead sometimes to the reorganisation of the wage relationship. By its mere existence, resistance as much as harsh and intelligent ways of coercion all testify the non-pacification of the wage labour.

A second approach, developed by Christian Thuderoz and Jacques Bellanger[35], has taken the decision to fully recognise micro-resistances at work by inserting them into a broader typology of oppositional behaviours. This figure n°3 shows how they articulate different dimensions of control and resistance.

|

Control by submission |

Control by accountability |

| opposition |

opposition |

| Weak |

Strong |

Weak |

Strong |

| Engagment |

Weak |

Withdrawal |

Recalcitrant |

Cynicism |

Rebellion |

| Strong |

Irreverence |

Militancy |

Distance |

Renouncement |

The overview contains some real heuristic virtues, since it reveals a seesaw between weak and strong opposition figures, and is linked to a mode of control exercised by management which recalls the notion of factory regime developed by Michael Burawoy in Politics of Production[36]. By articulating modes of control with the forms of employee commitment, this figure makes it possible to question a variety of situations. Moreover, the structural dimension is not absent, since the authors consider the ‘employment relationship’ as asymmetrical. Still, the pay/effort equation, the state of the labour market, as well as the socio-professional trajectory and age, will influence the relationship to work and determine how much some a willing to resist or misbehave.

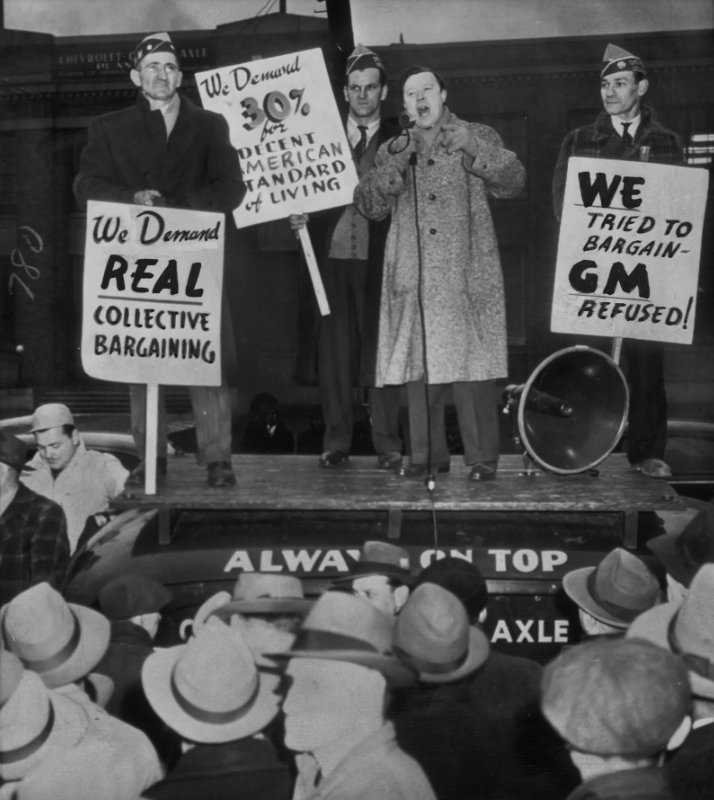

This leads us to some other observations. First of all, it should be noted that oppositional behaviour, and ‘rebellious subjectivity’ are not solely rooted in the experience of work. Let us recall Edward P. Thompson[37] on the origins of the formation of the working class when he highlighted how much the egalitarian desire for fairness have led the first generations of proletarian workers to organise themselves. Barrington Moore’s study on the social origins of obedience and revolt completes this picture, revealing in particular the presence of a ‘moral economy’ based on the values of justice, equity and reciprocity[38]. We could also recall the work of Charles Tilly, for whom the sentiment of injustice is the first driving force behind strike action and even to what may precede it, namely the refusal to submit oneself to management injunctions[39]. John Kelly, a British sociologist of industrial relations, extends this analysis by linking it to the lowering working conditions, caracterised by a constant demand for a very high level of involvement in the work activity[40]. For Kelly too, labour relations are structurally antagonistic, and therefore structurally unfair, which fuels hostility and opposition on the part of employees.

Moreover, these socio-historical interpretation around the moral economy have the merit of not closing the scope of analysis to the internal relations of the workshop or the firm, nor to the institutions and collective bargaining. Indeed, the study of work as a conflicting reality requires not only recognition of the asymmetrical nature of the ‘employment relationship’, as Thuderoz and Bellanger did, but also gains in legibility when class relations structured on the scale of society are included.

Certainly, the long post-war period was one of social progress based upon the extension of welfare, increasing real wages and recognition of social conflict and trade unions. But this happened thanks to geopolitical ‘cold war’ balance as well as the autonomous activity of the working class. The adoption of a middle-class standard norm of consumption may have nourished the belief that upward mobility was easy going. Still, the research about the ‘affluent worker’ done by John Goldthorpe and his team shows that a better living does not necessarily imply losing one’s class identity. However, over the last decades, this upward social mobility has become much more difficult, to that extent that self-employment or ‘using oneself against oneself’ to use French psychologist Yves Clot’s notion, does not help much [41]. Class barriers are difficult to break down, while the condition of the labouring class became more precarious at the corporate level as much as the professional career. The trend towards the degradation of work and labour, such as it was analysed by Harry Braverman [42] in 1975 continued during the 1990s. Since more than a decade, this socio-economic uncertainty also affects stable employment (especially in the public services, care and teaching) as well as skilled categories of the workforce such as engineers and technicians.

3 – Between holding out and burning out

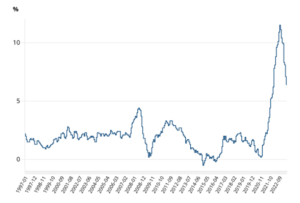

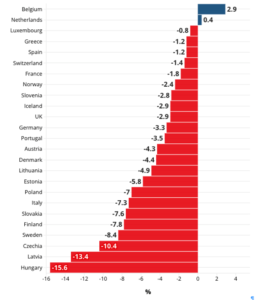

It is now established that the 2008 financial crisis had a negative effect on job quality in OECD countries[43]. Following Robert Castel, author of Les métamorphoses de la question sociale : une chronique du salariat (1995-2000)[44], a historical account of the salariat with a long durée analysis, one can observe a movement of casualisation of the ‘stabilised categories’ and the impoverishment of the unstable, precarious workers and thirdly, a growing group of ‘super-numeraries’ that are constrained to live in poverty without any perspective. Following Castel, these developments reflect the return of a ‘wage labour condition’ marked by severe or growing socio-economic insecurity. These evolutions were already underway during the last two decades of the 20th century through a rampant erosion of living standards facilitated by the disempowerment of trade unions. Harsher and degraded living conditions were not only caused by rising unemployment. In many European countries, employment policies followed the path of reduced social protection, lowering benefits and shortening the duration of receiving benefits as well as the increased conditionalities of entitlement. These policies mobilised the ‘reserve army’ in order to increase pressure to accept lower standards of employment[45]. For these reasons Bob Jessop wrote about a ‘Schumpeterian workfare state’[46] while French tandem Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval evoked an ‘ordo-liberal state’, referring to ‘ordo-liberalism’ as a kind state interventionism that supports the accumulation of capital[47].

In many sectors and companies, precarity coincides with substandard working conditions as we can notice in many European surveys. The surveys of the French department of the ministry of labour [48] allow us to observe that assembly line works increased a lot. From 1984 to 2016 the proportion of employees saying ‘their work pace is imposed by the automatic movement of a product or part’ rose from 2.6% to 18% of the total. This trend has now reached the service sector, where supermarkets, call centres and logistics have seen an increase in speed and mechanisation of the labour process. The proportion of employees who have to repeat the same tasks over and over again has increased from 27.5% in 2005 to 42.7% in 2016. Those who report having a work pace imposed by digital monitoring increased from 25% in 2005 up to 35% in 2016. The proportion that declare they frequently have to give up a task for ‘an unscheduled one’ increased from 48.1% in 1991 to 65.4% in 2016. At the same time, those reporting ‘a work pace imposed by an external demand requiring an immediate response’ increased from 28% in 1984 to 58% in 2016. Additionally, pressure is mounting thanks to interventions that are not necessarily consistent. The proportion of employees saying they receive conflicting orders rose from 41% in 2005 to 45% in 2016. As a result, solutions, often on an individual and informal basis need to be found. The number of employees who stated that a mistake or error could result in ‘sanctions’ has risen from 51.3% in 1991 to 63.1% in 2013. The increased responsibilities due to relational work with customers is putting even more pressure on their shoulders.

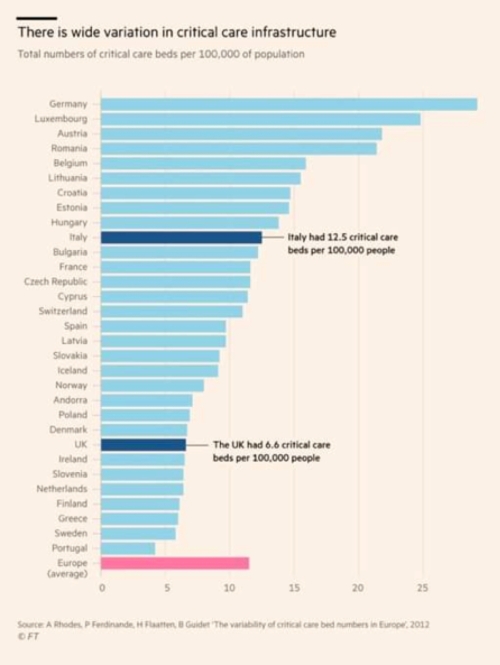

An equal trend of intensification can be observed, albeit to varying degrees, in several EU countries[49]. It is no exaggeration to say that there is a tendency to constantly increase the pressure on employees. The number who reported having continued to work, while being sick increased significantly during the last decade. In 2016, in France and the United Kingdom, almost six out of ten employees worked whilst being ill. This phenomenon, also known as presenteeism, affects less people in Germany (3/10) and Belgium (4/10), two countries with strong unions at the level of the shopfloor. In terms of work-life balance and working time flexibility, 60% to 70% of respondents (in countries such as Benelux, UK, Germany, France and Italy) declare they have worked at least one full weekend in the four weeks, whereas the proportion of employees was around 45% before the 2008 crisis. The working day is also getting longer: in France, 40% of respondents report having worked more than ten hours a day, at least twice in the past month[50].

Despite the introduction of new work organisations, ‘discretionary autonomy’ (the ability to personally decide how to carry out tasks) remains low. This can be seen as a consequence of lean management, which pursue rationalisation through demanding more effort in less time and with fewer resources. About one third of respondents in France, Germany, Belgium and the UK say they are unable to determine the pace of work. This is a huge minority. However, even more than a third say that they can never determine a break in their work by themselves. Monotonous tasks are still the daily fate for one quarter of the workforce. At the same time, the number of factors fixing the pace of work tends to increase. In France, quite close to the European average, 28% of respondents are confronted with two intensification factors, 24% with three and 18% with four or more. All of these figures have increased compared to the period between 2005 and 2010.

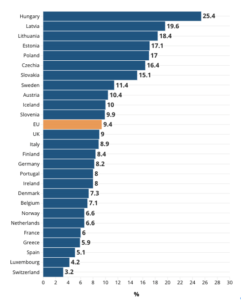

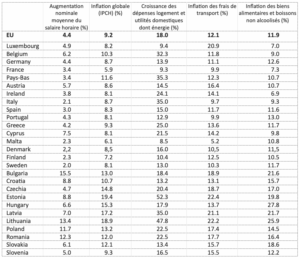

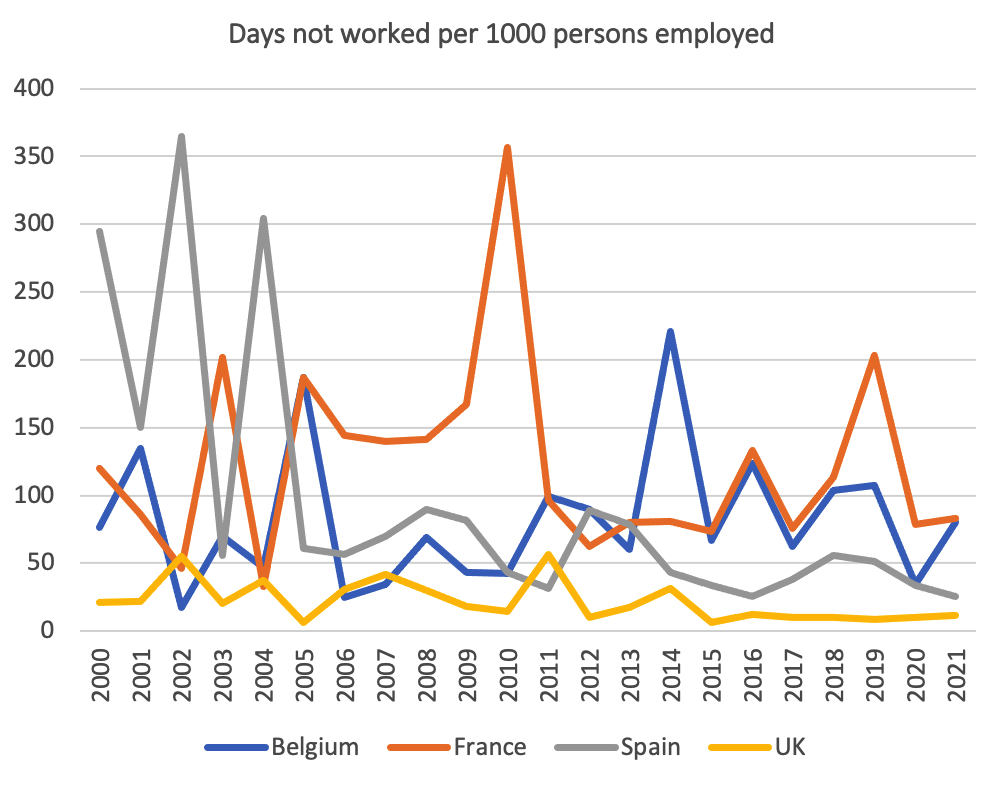

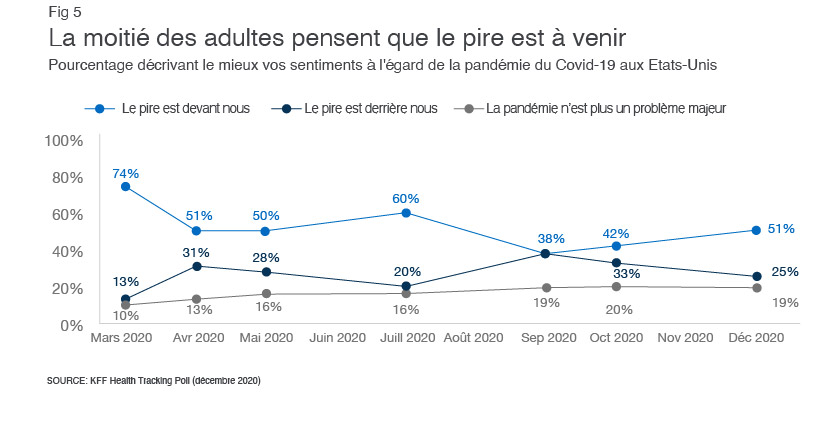

The intensification of work continues and that high pressure targets became unavoidable for almost 20% of the workforce. Beyond a group that is permanently exposed, another 30% to 40% of respondents admit being confronted with such a constrain for about a quarter to half of their working time. When we regroup both segments together, we can say that about 50% of the workforce is nowadays permanently or intermittently exposed to high work pressure. The table below shows how this phenomenon affects employees in different European countries.

Table 1 – Overview of work constraints and workload – European Working Conditions Survey (2017)

| |

France |

Belgium |

Germany |

United Kingdom |

| Are you subject to high work rates? |

• 24% almost all the time

• 30% between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

• 22% almost all the time

• 36%between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

• 20% almost all the time

• 43% between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

• 23% almost all the time

• 42% between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

| Does your job require you to work under very strict and tight deadlines? |

• 42% almost all the time

• 29%between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

• 41% almost all the time

• 34%between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

• 34% almost all the time

• 47% between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

• 42% almost all the time

• 38% between ¼ and ¾of the working time |

Source: European Working Conditions Survey, 2017 (survey was carried out in 2015)

How do employees behave given this tightening of constraints and demands on their work activity? Initially, most common attitude is to cope with it as best they can, to ‘put up with it’, so to speak. But for a significant proportion of the workforce, those exceptional situations tend to become an implicit standard and in the absence of actions improving working conditions, both bodies and minds are worn out and workers ends up exhausted.

It can be observed, in certain circumstances, from a high turnover rate, that the recurrent replacement of staff becomes a ‘functional’ social norm. Many young workers engage in low quality employment for a certain duration but will quit when they can’t bear the pressure anymore. For employers, this is not a problem as long as they can easily find other workers to engage into such intensified work. Such a regime of intensive labour mobilisation is characteristic for employment sectors that have been described as ‘low road’ in the Anglo-Saxon literature[51]. These ‘low road’ situations include call centres, cleaning, fast food (‘chain workers’) and handling activities in logistics. A survey about job satisfaction and well-being by Ambra Poggi and Claudia Villosio[52], observe quite evidently that jobs with poor autonomy, combining a sustained effort and low pay, high levels of working time flexibility without job security, is making employees much less satisfied regarding their jobs as well as less happy in life. It should also be noticed that most exposed to such working conditions are male unskilled workers, women in the service sector and elder workers.

Since some work situations also demand high quality performance, it will require stable teams with skilled employees and a guaranteed loyalty which is obtained on the basis of various transactions (salary amounts, bonuses and job security). In these circumstances, lean management cannot be so fussy. This is, at least, the interpretation of work situations described as ‘high road’, a metaphor for the way to sustainable, quality employment (Poggi & Villosio, 2015).

My hypothesis is that such a dualistic regime is now in crisis, as shown by the extent of the burn-out. Even if a common medical definition of this pathology is still lacking [53], the fact remains that a growing number of epidemiological studies are devoted to this issue. In Austria, a large survey carried out by general practitioners concluded that almost one in two employees is or has been affected by burn-out [54]. From the medical viewpoint, someone suffering a burn-out will go through different stages: at first, which seems non-pathological in itself, the employee’s conduct corresponds to over-commitment, with an attitude such as ‘I can handle everything’. However, the person neglects hobbies, personal needs, is sometimes irritable and may start to suffer from disordered sleep or lack of appetite. A second stage corresponds to denial – ‘I can still manage’ – but contains the seed of the awareness of problematic work behaviour. The person is trying to maintain this high involvement but will slip into social isolation and start to suffer from physical and psychological somatisation. The third stage is the one where the pathology of burn-out is openly declared, which corresponds to the emergence of phobias, anxieties and other symptoms of depression, to which is sometimes added complete social withdrawal, recurrent insomnia and above all the development of a feeling of exhaustion with an inability to continue working. The final stage occurs when a long sick leave has become inevitable.

According to this survey, out of 45% of people declared being affected by burnouts, the survey evaluates the proportion of people in stage 1 or 2 respectively at 18% and 15%, while 8% of people will slide into the third situation and 2% went as far as stop working for at least a couple of weeks. According to Marc Loriol[55], a French sociologist specialized in the study of health at work, burn-outs should be seen as a process embedded in social and professional contexts:

“Burn-outs results from the combination of a strong commitment to one’s activity and work situations where there are no a priori limits to the needs to be met. If the organisation demands more and more, or if work groups are unable to set these limits or to discuss the adequacy of means to an end, employees will burn out and end up by sick leave in order to keep a job that puts them under pressure at distance. Still, employees who are exhausted by pursuing an unattainable ideal end up, in order to protect themselves begin to develop cynical attitudes or to dehumanise others. As a result, they lose all professional self-esteem and undermine the meaning in their work. If this process is not interrupted by individual accommodation (transfer, retraining, search for forms of self-esteem outside of work, etc.) or collective accommodation (definition of less ambitious objectives, obtaining new room for manoeuvre), it can lead to forms of pathological depression.”[56]

In a 2016, a study by Mickael Rose based on a very large panel of more than 4000 respondents linked burn-outs to the lack of autonomy over workload[57]. Following their findings, it appears that several factors facilitate the onset of a burn-out: 1) the absence of a managerial policy that allows individuals to modulate their efforts, 2) a weak collegiality and solidarity within work teams, 3) the lack of professional training to better adjust to quantitative and qualitative demands. A particularly ‘pathogenic’ dimension seems to be the degree of depersonalisation of work combined with the impossibility to express one’s emotions at work.

Table 2 – Prevalence of burn out and degree of autonomy (Germany, 2015)

| Degree of autonomy |

Men |

Women |

| High |

6%

|

7%

|

| Rather high |

9%

|

8%

|

| Rather weak |

11%

|

13%

|

| Weak |

17%

|

15%

|

Source:Rose et al. (2016) p.36.

Overall, whether one adopts the point of view of an ‘epidemic disease’ or that of a ‘malaise’ specific to ‘fragilised’ people, the fact remains that the syndrome of exhaustion and is now at the forefront of the professional and academic literature.

The use of psychotropic substances is another phenomenon that tends to develop in the workplace. The second congress of French general practitioners about ‘Work, health and the use of psychotropic drugs’, held in 2017 discussed the question of the extent at which there is a causal link between the increased use of psychotropic drugs and the evolution of work[58]. Following the survey among the association’s member doctors, a vast majority of respondents consider that almost two out of three employees regularly use all kinds of drugs to ‘stay in the game’. These drugs range from ordinary painkillers to illegal substances (cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines) or legal drugs such as alcohol. More specifically, a majority also observed an increase in the abuse of opiate derivatives in recent years which seem to be linked with various forms of pain (elbow, back, etc.). “Today, our patients carry a mini-pharmacy with them and pass on tranquilizers among colleagues” explained a doctor who spoke at the congress.

According to their conclusions, this overconsumption is the result of the intensification of work in a context of social isolation, without mutual support and where the sense of community and sharing skills tend to diminish. This makes those exposed to high pressure even more vulnerable. While the consumption of psychoactive substances was primarily the result of professional situations such as stress and increased work demands, today professional rituals such as a shared lunch on Friday come into play in second place. The survey of doctors concludes that individuals seem increasingly helpless to cope with a high performance work culture and find no other way out than ‘doping for coping’. The main medical concern is that, in the absence of solutions, abusive over consumption use becomes a taboo, while the feeling of powerlessness will provoke a crisis in family environment and educational setting for children.

Can we conclude that ‘holding on’ or resilience is already a kind of resistance? Of course not, since the work activity continues to deliver the expected added value and contributes to the overall economic performance of the company. But when we take into account the subjectivity of employees, their relationship towards work, with many employees that continue to cope with targets and constraints, we also know that they tend to convince themselves that efforts will not be vain. But this type of acceptance is based upon denial and will feed a clinical situation that will end up being really pathological. In other words, ‘holding on’ is not so much making oneself resilient as it is the antechamber of an open crisis of one’s commitment to work hard.

4 – Governance of subjectivity and the return of critique upon labour

The non-pacification of work relations can also be analysed through the lens of management’s practices. Of course, management is far from an invariant since it may opt for putting more pressure upon employees as well as it concedes space for autonomy or accept some ‘constrained regulation’ through dialogue with trade union representatives. However, nowadays, certainly in France, the main trend in large firms in the manufacturing sector as well as in the services sector, including the public sector, is to rationalise activity following the recipe of lean management, with a constant search of increased work performances.

In the wake of permanent rationalisation, following Daniel Mercure, the regime of mobilisation of ‘passive agency’ with a workforce whose activity was governed by procedures and bureaucratic control was substituted by a regime conferring employees the role of performers. If the ‘executing agent’ was the typical figure of Taylorism, the post-Fordist regime of mobilisation is structured around the figure of the ‘assigned actor’, considered as responsible but endowed with versatility and reactivity[59]. During the last decade, we saw a new figure of a ‘self-regulated subject’ emerging which aim to mobilise, beyond the individual, the person at work. Oriented towards a strong sense of responsibility and commitment, based on empowerment, the individual ends up considering himself as an entrepreneur of himself and the author of his employability[60]. Subjectivity is represented as free of constraint, with an engagement in work through internalised high-performance requirements.

All these figures can be present in various ways, given that their functionality is strongly correlated with the content of work. Still, to me, the important question here is not to correlate these figures of ‘executing agent’, ‘assigned actor’ and ‘self-regulating subject’ according to job content, the type of organisation, but rather to question the degree of acceptance and internalisation of these figures. Our fundamental hypothesis remains unchanged, namely the fact that management and mobilisation regimes will give rise to critical reflexivity with regard to them. Let us recall, for example, that already at the end of the 1990s, surveys highlighted the mounting of critical views about work and its organisation, especially among skilled employees (clerks, technicians, engineers, supervisors even middle management).

More recent surveys reveal the permanence of such critical views. At a first level, we can observe that the employees may show lot of job satisfaction, even among employees under pressure[61]: 88% of respondents declared themselves satisfied with their work, of which 37% were ‘very satisfied’ and 51% ‘moderately satisfied’. The same survey also revealed that 20% were looking for a job elsewhere and, above all, there was a significant gap between the general opinion and the view on one’s own situation. Thus, 67% consider respectful treatment of staff to be important for job satisfaction, but only 31% consider themselves ‘satisfied’ in this respect. The same discrepancies can be observed regarding other fundamental dimensions of the working relationship:

- 63% consider pay to be crucial, but only 23% consider themselves satisfied in this respect;

- 58% consider job security to be an important issue for job satisfaction, but only 32% consider themselves satisfied in this respect.

Similar differences exist in terms of recognition of performance (48% versus 26%), about the content of the work (48% consider the work to be interesting, but only 27% consider theirs to be as such).

As was demonstrated before, in many cases, employees tend to rephrase their opinion in a positive way since this helps to ‘hold on better and longer’ because denial and recoding of bad feelings is needed to pursue full commitment because otherwise demotivation slides in.

Still something changed in the last decade since the governance of subjectivities transformed the issue of job satisfaction into an obligation of love where loving one’s work becomes a categorical moral imperative [62]. It is worthwhile to quote Steve Jobs explaining why: ‘(your) work will fill a large part of your life and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do your job. And the only way to do this is to love what you do’[63]. Therefore, we have moved from the slogan of ‘do what you love’ to ‘love what you do’…

Is this a surprise? Not really since both figures of ‘assigned actor’ as ‘self-regulated subject’ are calling upon powerful emotional and existential springs. Taylorism of subjectivity (in the sense of a prescription of the subjective relation to work) has gradually become a standard based on the sacredness of work that engages both soul and body. Therefore, we can speak about a bio-political dimension that goes beyond the search for recognition of one’s person, talents and contribution to the company. According to Kathi Weeks [64], this evolution is based on the mobilisation of values and resources borrowed from the traditional feminine role of ‘taking care with love’. As long as jobs are considered typically ‘feminine’, this emotional relation to the work effort remains invisible or naturalized. Care work is basically that, i.e; taking care which can only be done well ‘with love’, i.e. with a certain emotional commitment. However, the obligation to perform one’s work ‘with love’ has now spread to other sectors and activities. For Kathi Weeks, the trivialisation of loving your work has been accelerated by the increasing porosity between the spheres of work and non-work, facilitated by the use of nomadic objects and information and communication technologies[65]. Indeed, as long as the spheres of sentimental (romantic) love and the sphere of work were largely dissociated, with the exception of creative arts, they are now overlapping and sometimes merge, making it all the more difficult for individuals not to love too much what they do. In the end, it is not so much loving one’s work that counts as being able to continue to love it despite frustration and disappointment. The promises of love, joy or happiness at work are examples of what Lauren Berlant calls ‘cruel optimism’ because the object of desire overrides the goals that originally led you to it [66].

Are these people fooling themselves? Is this the über-example of voluntary servitude? Even if we can’t exclude this explanation, we should also retain the hypothesis of critical reflexivity, knowing that agency is always present to a certain extent. It is also important to integrate behaviour outside work and the relation towards career development. Both among younger workers as among those over forty, we can observe conduct of avoidance or rejection of jobs considered as meaningless [67]. In France, where student debt is not a massive phenomenon, many young people prefer, as long as the situation allows it (by staying with their parents or sharing the cost of living), a nomadic existence which reflects a refusal to commit to and pursue the effort of social promotion through work. Nowadays, life choices take into account aspects such as leisure, sports, art or travelling around the world, considering work in an instrumental way. The desire for autonomy may also lead individuals to favour non-submissive work settings, even if this means paying the price of a certain social marginality[68]. For those in their forties, some choose for a second career, mobilising vocational training if their status allows it. Sometimes, a refusal of promotion is accompanied by a commitment to activities with a strong ethical content, or even, in some cases, a quite late commitment to the trade unionism.

Some recent research among middle management, engineers and skilled technicians sheds new light on the question of the links between involvement and criticism of work [69]: those who adhere to the values of performance or the company culture are also the ones declaring that they limit their involvement to what is strictly necessary, while the ‘critical minds’ tend to correspond to those who want to appreciate their work for its content. They ‘keep the company going’, as long as the work situation is not too much in conflict with their critical mindset.

Other research shows the variety of tactics used in home care work, aiming both to preserve the care dimension and the relationship with the person being cared for, while at the same time seeking to make the best possible arrangements for working conditions and to secure the job [70]. In other cases, when work requires creativity and intelligence, we can observe levels of over-commitment that is difficult to maintain over time. The importance given to the value of work, by isolating it from the institution/organisation couple represented by the organisation or the employer, is then a source of involvement in itself, similar to the protestant work ethic. It is here that individuals find themselves trapped, especially when they have lost solidarity links with colleagues.

It is by having discovered these new emotional sources of productivity that management manufactured new ways of governance of subjectivities. However, by becoming an institutional narrative, this governance will reveal sooner or later its real nature, namely a sentimental manipulation, a trap, or even an emotional swindle. This is why it is important to continue search after contradictions inside the arrangements of subjectivity.

It is my certainty that those renewed regimes of mobilisation and governance, based on subjectivity and emotions will feed a renewed critique of heteronomy and alienation. The fact that this is not yet fully visible does not mean that it does not exist underneath. Each employee may, depending on his or her professional trajectory and experiences, made up of satisfactions and frustrations, evolve from adherence to misbehaviour and resistance, in relation to his or her position in the hierarchy, level of qualification, age, as well as collective group dynamics or the presence of collective action frameworks (unions, etc.).

Several recent surveys confirm the thesis of recurrent resistance to work as well as a continuous critical reflexivity towards work and management albeit both may vary, i.e. more or less contextual, radical or definitive. Specific research among industrial engineers shows how much the growth of managerial tasks, linked to project-based management, leads to a densification of work and reduces margins of autonomy regarding ‘noble’ technical tasks[71]. Of course, engineers complain about this trend and develop tactics to circumvent and distance themselves from managerialism (i.e. evaluation or performance measurement procedures). Other investigations among the cleaning industry demonstrate how low wage workers will mobilise sanitary standards, in addition to cunning and restraint, to challenge authority[72].

In the service sector, my own field research reveals the extent of mixed behaviour[73]. We identified several modes of action on the part of employees. In the hotel and catering sector, behaviour of waiters is based upon tacit alliances with customers: offering an extra drink or recording a less expensive order while serving a more substantial dish is prompting the customer to pay tips, which can accumulate to 20 or 30 euros per day. As pub-managers may ‘cut’ alcohol in cocktails for example, in order to increase their profits, waiters are doing the same, but regarding their employer. In supermarkets, similar forms of income capture can be found by turning a blind eye to theft. The French Employers’ Federation of Distribution and Trade does not like to publish about this, but training schemes for shopkeepers and middle level management pay a lot of attention to counteract losses from theft, which, according to training, can amount to a significant proportion of stocks. Damaging a package or marking a product as defective is a way of side-lining goods that can be used or resold.

Sometimes, resistance can also translate itself into deliberately unpleasant or repressive customer service. As some research has shown[74], the reception staff of public services may behave in a fussy manner, become overzealous or refuse to deliver the support a customer is asking. Train controllers may use all the latitude they have in applying the rules. Some will turn a blind eye to an infringement, even if it is difficult when they are under the gaze of colleagues, while others will mobilise the security forces. When a train is overcrowded, some may downgrade a business class carriage to an ordinary one, while others will systematically let people pile up each other into and repress with a certain disdain anyone who objects. This kind of behaviour comes close to ‘inverted resistance’ since it means the public service goals are deliberately not met. Still, from the viewpoint of the employees behaving that way, such an attitude is justified since resources for a fluent and good working public service are lacking. It is obvious that the relation to work, the ethos of service to the public and the existence of a professional culture introduce many variables, but the fact remains that the service relationship even in the era of rationalisation and highly formalised ‘customer relationship’ management, leaves room for different kinds of adjustments.

5 – By way of conclusion

Ten years ago, analysis according to which the collective worker is atomised while employees consent enthusiastically, even playfully, to the heteronomy of work, was a one-sided narrative. Even if it was true that the logic of lean management and high-performance work systems had become hegemonic, this does not mean that critical visions and behaviours existed and still do.

Ten years ago, as much as now, at least in France, it is still not easy to make this divergent analysis heard, also because sociology of consent and servitude is presented as compassionate, sometimes even very critical towards capitalism, especially when it develops a narrative that echoes ‘authentic’ speech on the part of employees, sometimes coupled with a trade union-oriented narrative complaining about the lack of awareness and consciousness of workers.

Ten years after the ‘Great recession’ and the financial crisis, the wage labour condition has not improved much in France nor in Europe. Restructuring, casualisation, unemployment, increased competition, blackmail and relocation, the application of digital control technologies, the logic of competence, and the development of managerial policies that make the love of work sacred, have certainly made life at work harder, more stressful and worrisome. These negative aspects may have been counterbalanced for a time by playful and creative dimensions, by a certain autonomy as well as the valorisation of one’s personal contribution and the patient expectations of (very selective) promotion. Of course, as long as employees continue to believe in this, it will be reflected in their behaviour. But what happens when disappointed hopes accumulate and a widespread sense of injustice gains ground?

More fundamentally, when many people need stimuli or psychotropic drugs, when they become sick because of their job, the first thing to recognise is that the social sphere around wage labour or paid work is by no means ‘pacified’. Intensifying work to an extent than people are not capable to sustain is indeed a form of aggression or violence, not only symbolically, since it physically hurts bodies and minds. Sooner or later, this kind of situations will not fail to give rise to reactions, both at the level of subjectivity, representations as regarding behaviour, .e. the way in which people work together and complete their work.

In view of the extent of the degradation of working conditions, we can formulate the hypothesis that critique of work now affects managers, whether they are executives or supervisors, as much as technicians or engineers, and even more so subordinate employees such as workers and employees. This critique does not imply that people no longer appreciate their work and its content; they can do so and still carry the value of work high. On the other hand, I am convinced that we are witnessing a return of critical and even ‘rebellious’ subjectivity that is directed as much towards management as at it targets the abstract logic of valorisation (like sacrificing everything for the purpose of a career) perceived as ‘cold’ and almost inhuman. This critique will be all the more vigorous as it is well understood that many misbehaviours and resistance practices are not able to change what has become unbearable ‘in the long run’. In such a situation, only ‘exit’ or moments of social revolt open up some perspective both on individual as collective level.

This collective dimension can emerge where it is not expected. When we understand the wage condition as a whole and observe how many workers and couples belonging to ‘lower France’ have difficulty finding housing, healthcare and healthy food and when we add to this the impoverishment of the ‘middle classes’ and their growing difficulties in becoming homeowners or sustaining their social status, the social revolt of the gilets jaunes becomes more easily understandable.[75] This social revolt of the invisible of peripheral France is a perfect example of how a vast accumulated anger ends up exploding brutally, far from the immediate work space. In that regard, the idea that a new kind of human being has emerged, manufactured by lean production, and that he/she will consent to work hard in order to consume as much as possible while keeping silent, sounds like a bizarre interpretation of contemporary reality[76]. As Yann Le Lann has shown, based on a sociological survey of the Gilets jaunes occupying the roundabouts[77], this tax revolt was at the origin of a spontaneous and unexpected plebeian mobilisation, fuelled by a lack of recognition of work, both at the level of wages (or social benefits), as well as the shrinking earnings of small entrepreneurs.

The question remains, which we have not addressed yet: how does resistance relate to more general social conflict, whether institutionalised or not. The most reasonable conclusion is that both sociological analyses as social actors have every interest in not turning its back on what happens at the level of concrete work and the subjectivities that are involved in it.

(achieved in Summer 2018, published spring 2020)

English translation by the author

Stephen BOUQUIN (°1968) is a historian by training, has a PhD in political sciences (University of Paris 8) and qualified as sociologist by the CNU (1999). From 2000 to 2010, he was a senior lecturer in sociology at the University of Picardie-Jules-Verne followed by a position of professor at the University of Evry Paris-Saclay. He was director of Centre Pierre Naville between 2011-2018, and has been the editor of the biannual journal Les Mondes du Travail (www.lesmondesdutravail.net) since it was launched in 2006. He has published several books, including Résistances au travail (2008) and participated in several European research programmes.

Footnotes & bibliography

[1]– The original French version was published in Daniel Mercure (coord.) (2020), Les transformations contemporaines du rapport au travail, University of Laval Press.

[2] – Crozier, Michel, De la bureaucratie comme système d’organisation, Archives européennes de sociologie, vol. 2 – pp. 18-52; Touraine, Alain, « Pouvoir et décision dans l’entreprise », in G. Friedmann, P. Naville, Traité de sociologie du travail, T. II, 1962, pp. 3-41; Touraine, Alain, L’évolution du travail ouvrier aux usines Renault, Paris, CNRS éditions, 1955.

[3]– By ‘exploitation’ I mean a relationship of surplus extraction by the company and its shareholders, via the non-remuneration of a segment of the working time. There has been a long debate in French sociology since Raymond Aron explained the impossibility to quantify and therefore to prove the real existence of tearing our wealth by a non-payment for it. (Aron

[4] – Gorz, André, (ed.), Critique de la division du travail, 1973; Gorz, André, Métamorphoses du travail, quête du sens, 1988.

[5] – Vincent, Jean-Marie, Le Travail. Entre le faire et l’agir, 1987, PUF, Paris; Vincent, Jean-Marie, ‘La domination du travail abstrait’, in Critiques de l’Economie Politique, n°1, October-December 1977. POSTONE

[6] – Negt, Oskar, Lebendige Arbeit, enteignete Zeit: Politische und kulturelle Dimensionen des Kampfes um die Arbeitszeit, 1987; Negt, Oskar, L’Espace public oppositionnel, 2007.

[7] – Castoriadis, Cornelius, Political Writings 1945-1997. The Questions of the Labour Movement (Volumes I and II), 2012.

[8] – Lütdke, Alf, Des ouvriers dans l’Allemagne du XXe siècle : le quotidien des dictatures, L’Harmattan, 2000; Alf Lüdtke, Eigen-Sinn : Fabrikalltag, ArbeitererfahrungenundPolitikvomKaiserreich bis in den Faschismus, 1993, 445p. For an introduction to Lütdke, see also Alexandra Oeser, ‘Penser les rapports de domination avec Alf Lüdtke’, in Sociétés Contemporaines, vol. 99-100, n° 3, 2015, pp. 5-16.

[9] – Bouquin, Stephen (ed.), Les Résistances au travail, Paris, Syllepse, 2008.Most of this work dates from the early 2000s and was not necessarily very visible, given the status of young researchers or doctoral students, or even students, who turned their summer jobs into a field of participant observation and collected information showing, even if the confidentiality of these practices was fiercely defended, that braking, loitering, stealing and even sabotage was still practiced.

[10] – Hatzfeld, Nicolas, Les gens d’usine. 50 ans d’histoire à Peugeot-Sochaux, 2001, see also Durand, Jean-Pierre and Hatzfeld Nicolas, La Chaîne et le Réseau, Peugeot-Sochaux, ambiances d’intérieur, éditions Page 2, Lausanne, 2002.

[11] – Durand, Jean-Pierre, La Chaîne invisible. Travailleur aujourd’hui: flux tendu et servitude volontaire, Paris, 2004.

[12] – Linhart, Danièle, Travailler sans les autres, Paris, 2009.

[13] – Beaud, Stéphane and Pialoux, Michel, Retour sur la condition ouvrière, Enquête aux usines Peugeot de Sochaux-Montbéliard, Paris, 1999.

[14] – Bouquin, Stephen, La Valse des écrous. Labour, Capital and Collective Action in the Automobile Industry, Syllepse, 2006. See in particular chapters 1 (L’Archipel perdu, pp. 21-34) and 2 (De la voie unique à la diversité des modèles? , pp. 34-46).

[15] – Smith, Tony, Technology and Capital in the Age of Lean Production: A Marxian Critique of the ‘New Economy’, New York, SUNT, 2000; Bouquin, Stephen, 2006, op.cit; Bouquin S. e.a., Temps durs et dur travail. Un retour critique sur les modèles productifs à l’ère néo-libérale », in Jacquot Lionel, Higelé, Jean-Paul, Lhotel Hervé, Nosbonne, Christophe, Formes et structures du salariat : crise, mutation, devenir, 2011, pp. 110-123.

[16] – Examples can be found in the pharmaceutical industry as well as in the automobile sector. See Muller Séverin, ‘Modes de production du médicament générique et conditions d’emplois’, La nouvelle revue du travail [Online], 12 | 2018, online 01 May 2018, accessed 31 October 2019. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/nrt/3501; DOI: 10.4000/nrt.3501 See also, for the automotive sector, Bouquin S., La valse des écrous. Travail, capital et action collective dans le secteur automobile, Syllepse, 2006.

[17] – Bouquin S. (2006), ‘Visibilité et invisibilité des luttes sociales: question de quantité, de qualité ou de perspective?’, in Cours-Salies P., Lojkine J.,Vakaloulis M. (2006), Nouvelles Luttes de Classe, Actuel Marx, PUF, 2006, pp. 103-112.

[18] – Following the approach of James C. Scott, then still little known in France, who highlight the existence of a hidden narrative that is only expressed behind the back of power. See Scott, James C., Domination and the Arts of Resistance. The Hidden Transcript, 1990.

[19] – Baudelot, Christian and Gollac, Michel, Travailleur pour être heureux, Seuil, Paris, 2003. See in particular pp. 277-297.

[20] – Passeron, Jean-Claude, Le Raisonnement sociologique. L’espace de raisonnement naturel non popperien, Paris, Nathan, 1991.

[21] – Bouquin, Stephen, ‘Les résistances au travail entre domination et consentement’, in Bouquin, Stephen op.cit. 2008, p. 44; see also Bouquin, S., ‘Les résistances au travail. Il est temps de sortir de l’imprécision’, in Caldéron, José-Angel and Cohen, Valérie (eds.), Qu’est-ce que résister? Usages et enjeux d’une catégorie d’analyse sociologique, 2014, p. 111-123.

[22] – See in particular Flocco, Gaëtan, Les cadres, des dominants très dominés. Pourquoi les cadres acceptent leur servitude, Raisons d’agir, 2015.

[23] – Spitaels, Guy, Les conflits sociaux en Europe: grèves sauvages, contestations et rajeunissement des structures, Marabout, 1971. For a review, see Bachy Jean-Paul, Guy Spitaels, Les conflits sociaux en Europe, Marabout Service collection, 1971. In: Sociologie du travail, 14ᵉ année n°4, Octobre- décembre 1972. pp. 476-478.

[24] – Farcy Isabelle, Ajustement et oppositions masquées par mes intérimaires, in Bouquin S., op.cit., (2008), pp. 157-178; Letexier Jean-Yves, Autonomie et resistances chez les intérimaires, Mémoire Master, Université de Picardie Jules Verne, 2012.

[25] – Clot, Yves, Travail et pouvoir d’agir, Presses Universitaires de France, 2014.

[26] – Burawoy, Michael, Produire le consentement. [édit orig. Manufacturing Consent: Changes in the Labor Process Under Monopoly Capitalism, 1979], Les Prairies ordinaires, 2015, 303p.

[27] – Fournier Pierre (1996), ‘Deux regards sur le travail ouvrier’. In: Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales. Vol. 115, décembre 1996. Les nouvelles formes de domination dans le travail (2), pp. 80-93. https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.1996.3206 ; www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1996_num_115_1_3206